Love,Life,and "Leftover Ladies"in Urban China Jing You,.'Xuejie Yi and Meng Chen3 1.School of Agricultural Economics and Rural Development,Renmin University of China 2.National School of Development,Peking University 3.School of Sociology and Political Science,Shanghai University Abstract The Chinese urban society in recent years has shown rising age at first marriage and declining marriage rates,especially among professional females with at least college degrees in their late 20s or their 30s.We exploit two nationally representative datasets over the period 2008-2012 and investigate the determinants of forming marriage for urban women aged 27 or above who are termed "leftover".We estimate a recursive and dynamic mixed-equation model to describe women's joint decisions on career,education and marriage.This considers various traits including demographic characteristics,wealth,work-related indicators, personality,attitudes and expectation,physical and facial attractiveness,leisure activities, personal and parental social status,local gender identity norms and marriage market conditions.We find"marital college-discount":college education reduces the probability of marriage by 2.88%-3.6%and a postgraduate degree further oppresses it by 8.4%-10.4%. Counterfactual analysis indicates monotonicity,complementarity and substitution in multidimensional matching patterns.Patriarchy still appears to prevail. Keywords:marriage,gender,education,earnings,China JEL classification:J12.J16.O53 Corresponding author:Dr Jing You.Permanent Address:School of Agricultural Economics and Rural Development,Renmin University of China,59 Zhongguancun Street,Beijing 100872,China.Email: iing.vou@ruc.edu.cn.Tel.:+86-(0)10-6251-1061.Fax:+86-(0)10-6251-1064.Personal web: http://jingyouecon weebly com/.We are grateful to participants in the HECER (Helsinki Center of Economic Research)Labour and Public Economics Seminar held on 4 June 2015,and the Labour and Development Seminar at Renmin University of China held on 8 January 2016 for insightful discussion and helpful comments on an earlier draft.All remaining errors are,of course,the sole responsibility of ours

1 Love, Life, and “Leftover Ladies” in Urban China Jing You,1, * Xuejie Yi2 and Meng Chen3 1. School of Agricultural Economics and Rural Development, Renmin University of China 2. National School of Development, Peking University 3. School of Sociology and Political Science, Shanghai University Abstract The Chinese urban society in recent years has shown rising age at first marriage and declining marriage rates, especially among professional females with at least college degrees in their late 20s or their 30s. We exploit two nationally representative datasets over the period 2008-2012 and investigate the determinants of forming marriage for urban women aged 27 or above who are termed “leftover”. We estimate a recursive and dynamic mixed-equation model to describe women’s joint decisions on career, education and marriage. This considers various traits including demographic characteristics, wealth, work-related indicators, personality, attitudes and expectation, physical and facial attractiveness, leisure activities, personal and parental social status, local gender identity norms and marriage market conditions. We find “marital college-discount”: college education reduces the probability of marriage by 2.88%-3.6% and a postgraduate degree further oppresses it by 8.4%-10.4%. Counterfactual analysis indicates monotonicity, complementarity and substitution in multidimensional matching patterns. Patriarchy still appears to prevail. Keywords: marriage, gender, education, earnings, China JEL classification: J12, J16, O53 * Corresponding author: Dr Jing You. Permanent Address: School of Agricultural Economics and Rural Development, Renmin University of China, 59 Zhongguancun Street, Beijing 100872, China. Email: jing.you@ruc.edu.cn. Tel.: +86-(0)10-6251-1061. Fax: +86-(0)10-6251-1064. Personal web: http://jingyouecon.weebly.com/. We are grateful to participants in the HECER (Helsinki Center of Economic Research) Labour and Public Economics Seminar held on 4 June 2015, and the Labour and Development Seminar at Renmin University of China held on 8 January 2016 for insightful discussion and helpful comments on an earlier draft. All remaining errors are, of course, the sole responsibility of ours

Love,Life,and "Leftover Ladies"in Urban China Mediocrity is the virtue of women. Admonitions for Women(80 CE),by BAN Zhao(45-116 CE,China) 1.Introduction After more than three decades of economic reform,marriage remains universal and early in China (Ji and Yeung,2014;Jones and Gubhaju,2009).Yet,as with the other spheres of modern Chinese life,the marriage market has been evolving as part of the rapid,and, sometimes radical,socioeconomic transitions.Among the changes,the most visible features include two seemingly paradoxical phenomena:While the urban population of every province of the country reports higher-than-one sex ratio of unmarried men over unmarried women,urban women in their late 20s or 30s show decreasing rates of marriage formation. The 2010 Census suggests that three in ten urban women aged 25-29,long the most common age for urban women's first marriage in the Chinese tradition,had never been married, although there were 1.19 million more men than women in cities,contradicting the positive impact of sex ratio on the likelihood of women's marriage widely found in other countries (e.g.,U.S.in Angrist,2002 and Abramitzky et al.,2011). Researchers from various disciplinary backgrounds have documented the different situations Chinese men and women may face in the future.On the one hand,men of lower social status and less education will confront a deteriorating marital squeeze,with the rate of male bachelorhood predicted to peak around 2050(Guilmoto,2012;Huang,2014;Jiang, 2014);on the other,urban women,typically the well-educated,have to weigh the chance of marriage formation against their personal development in the public sphere (Ji,2015;Tian, 2013:Yu and Xie,2015). 2

2 Love, Life, and “Leftover Ladies” in Urban China Mediocrity is the virtue of women. Admonitions for Women (80 CE), by BAN Zhao (45-116 CE, China) 1. Introduction After more than three decades of economic reform, marriage remains universal and early in China (Ji and Yeung, 2014; Jones and Gubhaju, 2009). Yet, as with the other spheres of modern Chinese life, the marriage market has been evolving as part of the rapid, and, sometimes radical, socioeconomic transitions. Among the changes, the most visible features include two seemingly paradoxical phenomena: While the urban population of every province of the country reports higher-than-one sex ratio of unmarried men over unmarried women, urban women in their late 20s or 30s show decreasing rates of marriage formation. The 2010 Census suggests that three in ten urban women aged 25-29, long the most common age for urban women’s first marriage in the Chinese tradition, had never been married, although there were 1.19 million more men than women in cities, contradicting the positive impact of sex ratio on the likelihood of women’s marriage widely found in other countries (e.g., U.S. in Angrist, 2002 and Abramitzky et al., 2011). Researchers from various disciplinary backgrounds have documented the different situations Chinese men and women may face in the future. On the one hand, men of lower social status and less education will confront a deteriorating marital squeeze, with the rate of male bachelorhood predicted to peak around 2050 (Guilmoto, 2012; Huang, 2014; Jiang, 2014); on the other, urban women, typically the well-educated, have to weigh the chance of marriage formation against their personal development in the public sphere (Ji, 2015; Tian, 2013; Yu and Xie, 2015)

While the issue of"surplus men"is clearly linked to the heavily skewed sex ratio,the term "leftover women"has been disseminated by the state media ever since 2007 to label women who are aged 27 or above but remain single.The "age threshold"then was reasserted by the All-China Women's Federation in their official report of the 2010 National Marriage Survey.2 As the gender-specific label grows into a social issue,concern about their daughters' marital plight has led anxious parents to make frequent visits to dating markets(Sun,2012). Meanwhile,the constructed phenomenon of"leftover women"has been widely covered in mass media both within China and overseas.3 Despite intense interest in the issue,serious academic research that directly addresses the phenomenon is limited.A few sociologists have approached the issue using qualitative interviews and revealed the struggle of"leftover"between modernity and tradition,along with their multiple sources of pressure connected with parents,the labour market,and potential male partners (Fincher,2014;Gaetano,2009;Ji,2015;To,2013).In comparison, quantitative studies tend(rather than treating it as an independent event)to describe marriage as an optimal decision maximising individuals'utility and to cover the issue of "leftover" women in analysis of marriage timing or examine the relationship between education and marriage formation(Yu and Xie,2015).Comparing men and women born respectively in the 1960s and 1970s,Tian(2013)found that the effect of education on marriage timing had been stable in a path-dependent marriage market where non-marriage receives social penalty.Qian and Qian (2014)and Wu and Liu (2014),respectively from a sociologist's and economist's view point,approached the issue in a more straightforward fashion,yet the discussion is still limited to the effect of education on marriage formation.The issue of"leftover women"is in need of a comprehensive investigation in order to provide both a more systematic description Or"leftover ladies"(both meaning shengm in Chinese).We use them interchangeably throughout the text. 2 According to the 2010 Narional Marriage Survey conducted in 31 provinces by the All-China Women's Federation (a government-sponsored mass organisation),90%of men thought women should marry before 27;6%considered the ideal time at 25-27;only 1%believed the best marital age for a woman was 31-35. 3 For example,BBC News Magaine on21 February 2013,the Economist on 3 May,2014,and the Guardian on 5 June 2014. 3

3 While the issue of “surplus men” is clearly linked to the heavily skewed sex ratio, the term “leftover women”1 has been disseminated by the state media ever since 2007 to label women who are aged 27 or above but remain single. The “age threshold” then was reasserted by the All-China Women’s Federation in their official report of the 2010 National Marriage Survey. 2 As the gender-specific label grows into a social issue, concern about their daughters’ marital plight has led anxious parents to make frequent visits to dating markets (Sun, 2012). Meanwhile, the constructed phenomenon of “leftover women” has been widely covered in mass media both within China and overseas.3 Despite intense interest in the issue, serious academic research that directly addresses the phenomenon is limited. A few sociologists have approached the issue using qualitative interviews and revealed the struggle of “leftover” between modernity and tradition, along with their multiple sources of pressure connected with parents, the labour market, and potential male partners (Fincher, 2014; Gaetano, 2009; Ji, 2015; To, 2013). In comparison, quantitative studies tend (rather than treating it as an independent event) to describe marriage as an optimal decision maximising individuals’ utility and to cover the issue of “leftover” women in analysis of marriage timing or examine the relationship between education and marriage formation (Yu and Xie, 2015). Comparing men and women born respectively in the 1960s and 1970s, Tian (2013) found that the effect of education on marriage timing had been stable in a path-dependent marriage market where non-marriage receives social penalty. Qian and Qian (2014) and Wu and Liu (2014), respectively from a sociologist’s and economist’s view point, approached the issue in a more straightforward fashion, yet the discussion is still limited to the effect of education on marriage formation. The issue of “leftover women” is in need of a comprehensive investigation in order to provide both a more systematic description 1 Or “leftover ladies” (both meaning shengnv in Chinese). We use them interchangeably throughout the text. 2 According to the 2010 National Marriage Survey conducted in 31 provinces by the All-China Women’s Federation (a government-sponsored mass organisation), 90% of men thought women should marry before 27; 6% considered the ideal time at 25-27; only 1% believed the best marital age for a woman was 31-35. 3 For example, BBC News Magazine on 21st February 2013, the Economist on 3rd May, 2014, and the Guardian on 5th June 2014

of the so-called "leftover women"in urban China,and a more nuanced understanding of how their educational background,career,and marriage formation are intertwined under the Chinese "modern-traditional mosaic"(Ji,2015a) Capitalising data from three of the Chinese General Social Surveys (2008,2010,and 2011)and two waves of the China Family Panel Survey(2010 and 2012),this paper explores the inter-dependent relationship between three changes for Chinese urban women,namely career,education,and marriage decisions.It is worth noting that the existing literature predicts either negative or positive two-way associations among the three.We answer the following questions:1)what are the likely causes of the quickly growing number of female singles in urban China,many of whom are college or post-college educated with decent earnings?;2)is China different from other countries where similar trends are also observed, such as the U.S.(Isen and Stevenson,2010)and East Asian countries sharing similar traditional gender ideology as China (e.g.,Japan and South Korea in Hwang,2016)?;3)do declining female marriage rates in urban China,especially among the college and post-college educated,reflect long-standing gender inequality or signal rising feminism as women's education might lead to more progressive attitudes on career and/or life?;and,4)is marriage delayed or forgone for the so-called "leftover women"while acquiring more educational attainments? The remainder of this paper is scheduled as follows.The next section reviews past relevant studies in order to provide an introduction of the demographic and socioeconomic changes facing urban women in China and to tease out possible explanations of women's marriage formation.Section 3 describes datasets and variables.Section 4 sets up the analytical framework,with the results are to be presented in Section 5.Section 6 concludes. 2.Background and previous studies 4

4 of the so-called “leftover women” in urban China, and a more nuanced understanding of how their educational background, career, and marriage formation are intertwined under the Chinese “modern-traditional mosaic” (Ji, 2015a). Capitalising data from three of the Chinese General Social Surveys (2008, 2010, and 2011) and two waves of the China Family Panel Survey (2010 and 2012), this paper explores the inter-dependent relationship between three changes for Chinese urban women, namely career, education, and marriage decisions. It is worth noting that the existing literature predicts either negative or positive two-way associations among the three. We answer the following questions: 1) what are the likely causes of the quickly growing number of female singles in urban China, many of whom are college or post-college educated with decent earnings?; 2) is China different from other countries where similar trends are also observed, such as the U.S. (Isen and Stevenson, 2010) and East Asian countries sharing similar traditional gender ideology as China (e.g., Japan and South Korea in Hwang, 2016)?; 3) do declining female marriage rates in urban China, especially among the college and post-college educated, reflect long-standing gender inequality or signal rising feminism as women’s education might lead to more progressive attitudes on career and/or life?; and, 4) is marriage delayed or forgone for the so-called “leftover women” while acquiring more educational attainments? The remainder of this paper is scheduled as follows. The next section reviews past relevant studies in order to provide an introduction of the demographic and socioeconomic changes facing urban women in China and to tease out possible explanations of women’s marriage formation. Section 3 describes datasets and variables. Section 4 sets up the analytical framework, with the results are to be presented in Section 5. Section 6 concludes. 2. Background and previous studies

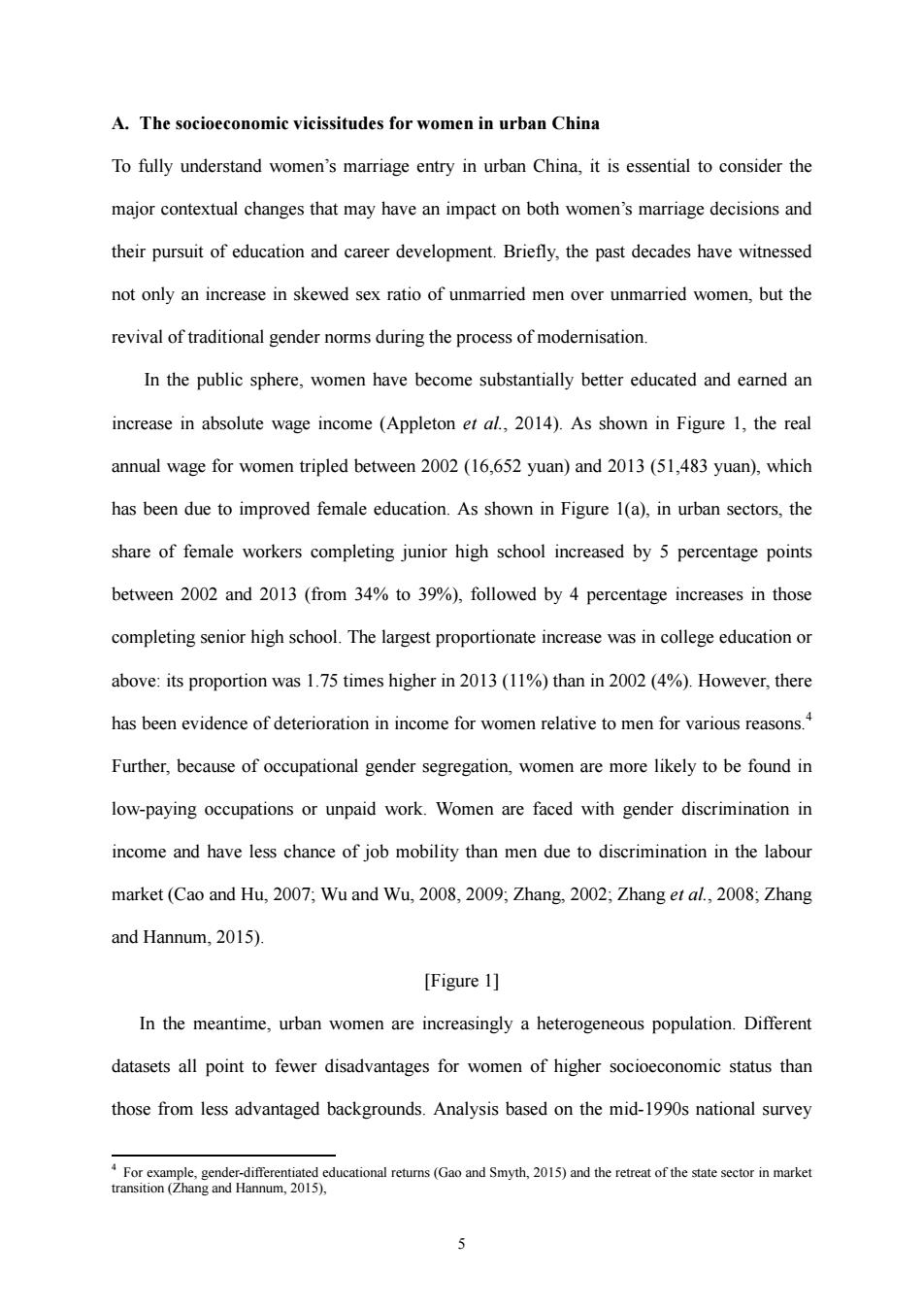

A.The socioeconomic vicissitudes for women in urban China To fully understand women's marriage entry in urban China,it is essential to consider the major contextual changes that may have an impact on both women's marriage decisions and their pursuit of education and career development.Briefly,the past decades have witnessed not only an increase in skewed sex ratio of unmarried men over unmarried women,but the revival of traditional gender norms during the process of modernisation. In the public sphere,women have become substantially better educated and earned an increase in absolute wage income (Appleton et al.,2014).As shown in Figure 1,the real annual wage for women tripled between 2002(16,652 yuan)and 2013(51,483 yuan),which has been due to improved female education.As shown in Figure 1(a),in urban sectors,the share of female workers completing junior high school increased by 5 percentage points between 2002 and 2013(from 34%to 39%),followed by 4 percentage increases in those completing senior high school.The largest proportionate increase was in college education or above:its proportion was 1.75 times higher in 2013(11%)than in 2002(4%).However,there has been evidence of deterioration in income for women relative to men for various reasons.4 Further,because of occupational gender segregation,women are more likely to be found in low-paying occupations or unpaid work.Women are faced with gender discrimination in income and have less chance of job mobility than men due to discrimination in the labour market(Cao and Hu,2007:Wu and Wu,2008,2009;Zhang,2002;Zhang et al.,2008;Zhang and Hannum,2015). [Figure 1] In the meantime,urban women are increasingly a heterogeneous population.Different datasets all point to fewer disadvantages for women of higher socioeconomic status than those from less advantaged backgrounds.Analysis based on the mid-1990s national survey 4For example,gender-differentiated educational retums(Gao and Smyth,2015)and the retreat of the state sector in market transition (Zhang and Hannum,2015)

5 A. The socioeconomic vicissitudes for women in urban China To fully understand women’s marriage entry in urban China, it is essential to consider the major contextual changes that may have an impact on both women’s marriage decisions and their pursuit of education and career development. Briefly, the past decades have witnessed not only an increase in skewed sex ratio of unmarried men over unmarried women, but the revival of traditional gender norms during the process of modernisation. In the public sphere, women have become substantially better educated and earned an increase in absolute wage income (Appleton et al., 2014). As shown in Figure 1, the real annual wage for women tripled between 2002 (16,652 yuan) and 2013 (51,483 yuan), which has been due to improved female education. As shown in Figure 1(a), in urban sectors, the share of female workers completing junior high school increased by 5 percentage points between 2002 and 2013 (from 34% to 39%), followed by 4 percentage increases in those completing senior high school. The largest proportionate increase was in college education or above: its proportion was 1.75 times higher in 2013 (11%) than in 2002 (4%). However, there has been evidence of deterioration in income for women relative to men for various reasons.4 Further, because of occupational gender segregation, women are more likely to be found in low-paying occupations or unpaid work. Women are faced with gender discrimination in income and have less chance of job mobility than men due to discrimination in the labour market (Cao and Hu, 2007; Wu and Wu, 2008, 2009; Zhang, 2002; Zhang et al., 2008; Zhang and Hannum, 2015). [Figure 1] In the meantime, urban women are increasingly a heterogeneous population. Different datasets all point to fewer disadvantages for women of higher socioeconomic status than those from less advantaged backgrounds. Analysis based on the mid-1990s national survey 4 For example, gender-differentiated educational returns (Gao and Smyth, 2015) and the retreat of the state sector in market transition (Zhang and Hannum, 2015)