and nontradable goods within countries-when there are divergences in relevant national rates of inflation. Divergences in national rates of inflation,however,are not the only oure of possible disturbance to international transactions.Real disturbances-changes in the underlying demand for or supply of particular goods and services -call for correction through the price mechanism Flexible exchange rates in some circumstances can help to bring about this adiustment.Indeed,when factor prices in nominal terms resist decline,and where some "money illusion"exists,movements in exchange rates may be the most efficient way to bring about the required decline in real factor prices This distinction between correction for divergence in inflation rates and adiustment to changes in real variables is crucial.for it indicates that changes in pominal exchange rates under a flexible rate system ca plausib led toa wide range of changes"exchange rate (changes in exchange rates corrected for inflation differentials),from none at all to a change fully equivalent to the change in nominal rates.In contrast to the impression someti conveyed ina literature preoccupied with purchasing power parity,we should not be surprised either in theory or in reality,to find a variety of changes in real rates corresponding to any ofdisturbances. An exchange rate is the rate at which one money exchanges for another.It therefore for foreign goods and services.Domestic demand for foreign securities and foreign demand for domestic securities are also important factors in the foreign exchange market.Indeed,the urent fashion the that"price"that cears the market with to the holding of foreign assets in national portfolios.It is admitted that over time exchange rates can have an important effect on investment at home and abroad.bence on net foreign investment,hence on foreign trade.But since the time it takes for investment flows to respon to differences in relative yield is very much longer than the time it takes for market prices to adjust to changes in asset preferences,portfolio balance considerations are thought to exercise the dominant short-rn ange rates.It is only over time that changes in th current account balance.which is equal to net foreign investment,can correct portfolio imbalances with respect to the holding of foreign assets. short-run influence of portfolio considerations on exchange rates,except tautologically. Imbalances in current p ments mayso influence expe ns about future exchang e rate (hence today's re to h securities)that a major role in exchange rate determination must 32

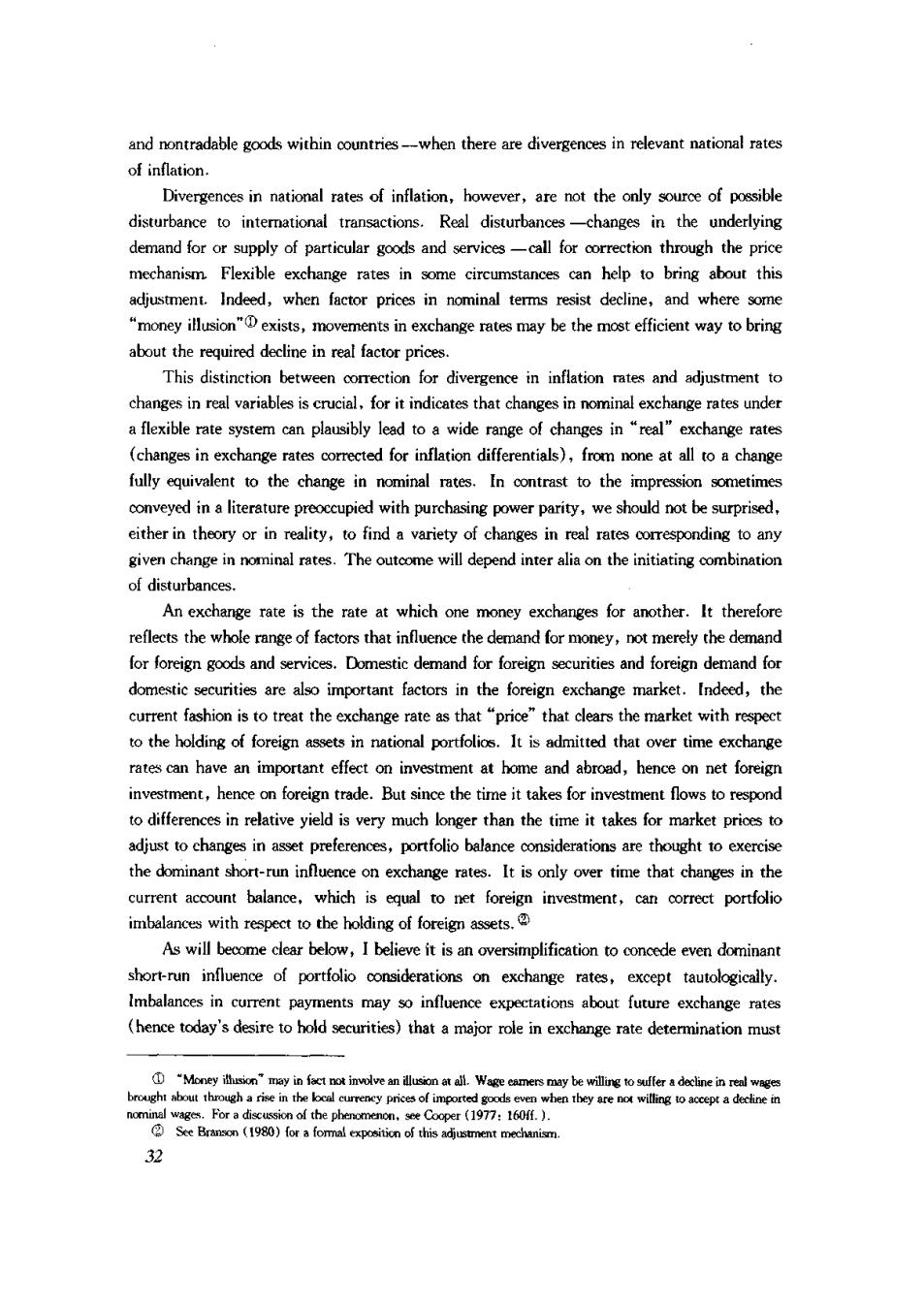

be given to imbalances in goods and services that are perceived to be nonsustainable.These explanations for exchange rate determination,properly considered,are not alternatives at all, but different aspects of the same underlying process whereby perceptions are translated into and expectations in tu are translatedinto market prices. Exchange Rate Developments,1973-1980 Let us tum from these analytical considerations to the events of 1973-1980.If we abstract from week-to-week movements,exchange rate movements are not that difficult to explain.Newspapers quote bilateral exchange rates,such as that between the german mark and the U.S.dollar.What is important for aoury'sonmy however,is not one single exchange rate,but some average of all relevant exchange rates.This average can be called the "effective"exchange rate.It is usually a weighted average of bilateral exchange rates,where the weights trading pattern of the outry in which we are interested.or sometimes to the trade of a group of oountries.(This kind of weighting obviously focuses on trade.A different setof weights would be appropriate if we weretofocus predominantly on financial transactions.)Second,as already noted,differences in national inflation rates may alter exchange rates simply to avoid affecting relative prices between or within.A change inan exchange rate orected for differential is called the change in the“real exchange rate With these distinctions in mind,consider the exchange rate of the U.S.dollar during the dollar took quite a beating in exchange markets during this period.It therefore will comne as a eat surprise to many that the effective exchange rate of the dollar relative to currencies of tries shwed no change in December its position in March 1973,when generalized floating began following the February 1973 devaluation of the dollar Inclusion of the currencies of developing countries in the "effective"rate would show an appreciationof the dolar over this period There were some ups and downs in the value of the dollar during this period,but they were o large and they followed amost textbook pattem in their movements.The effective rate appreciated mdestly in 1973 and aain in 1975-197:it depreciated in 1977-1978and appreciated slightly in 1979-1980 (see Table 1-1).The real effective exchange rate of the dollar (prices tomeasure) wed a similar pattem,except for an initial depreciation of the dollar in 1973.when inflation rates in other industrial countries sharply exceeded those in the United States. interrelations have begun to be reoognised.See for examole.Dombuvch 1980)and Brancon's 1980)

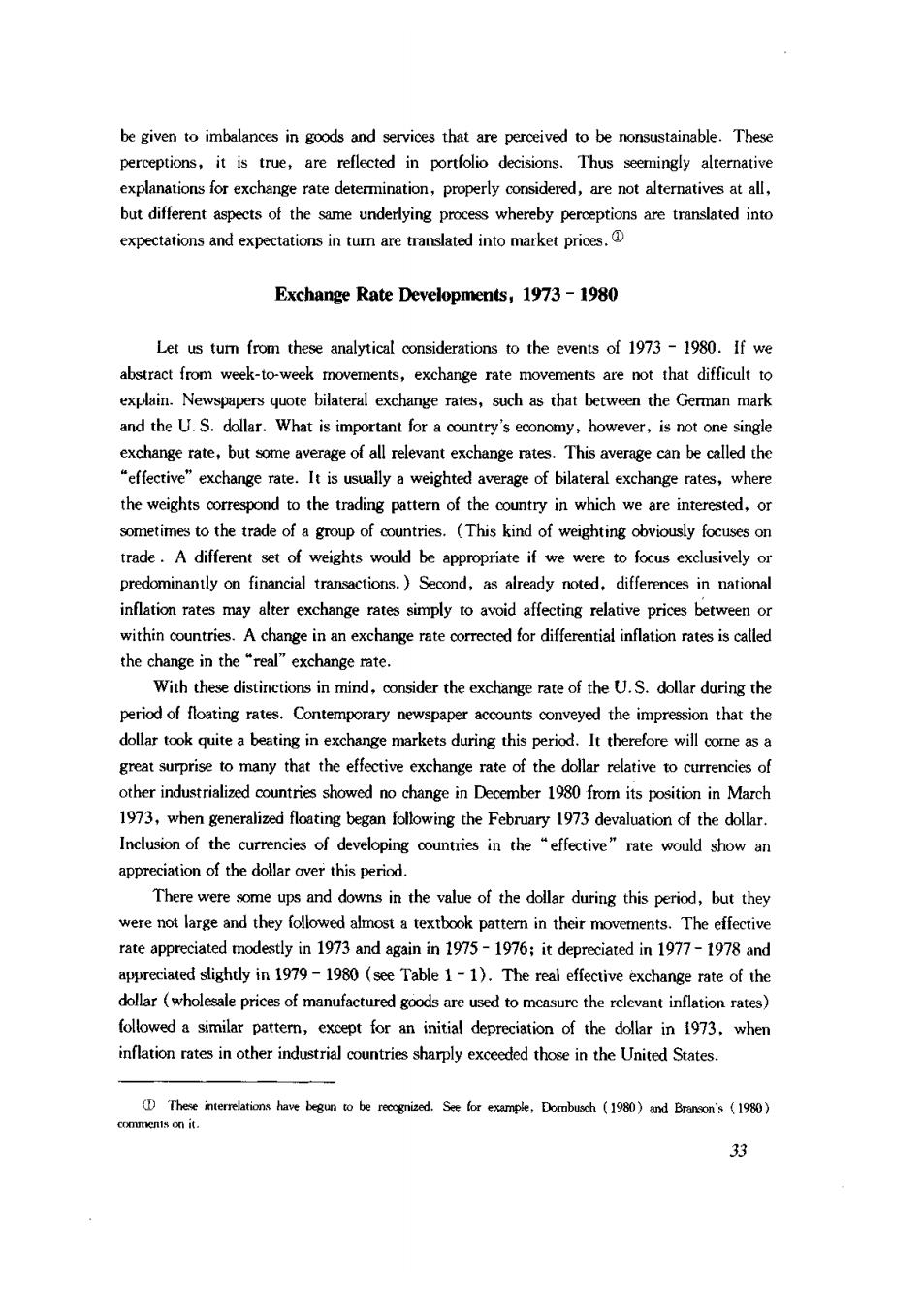

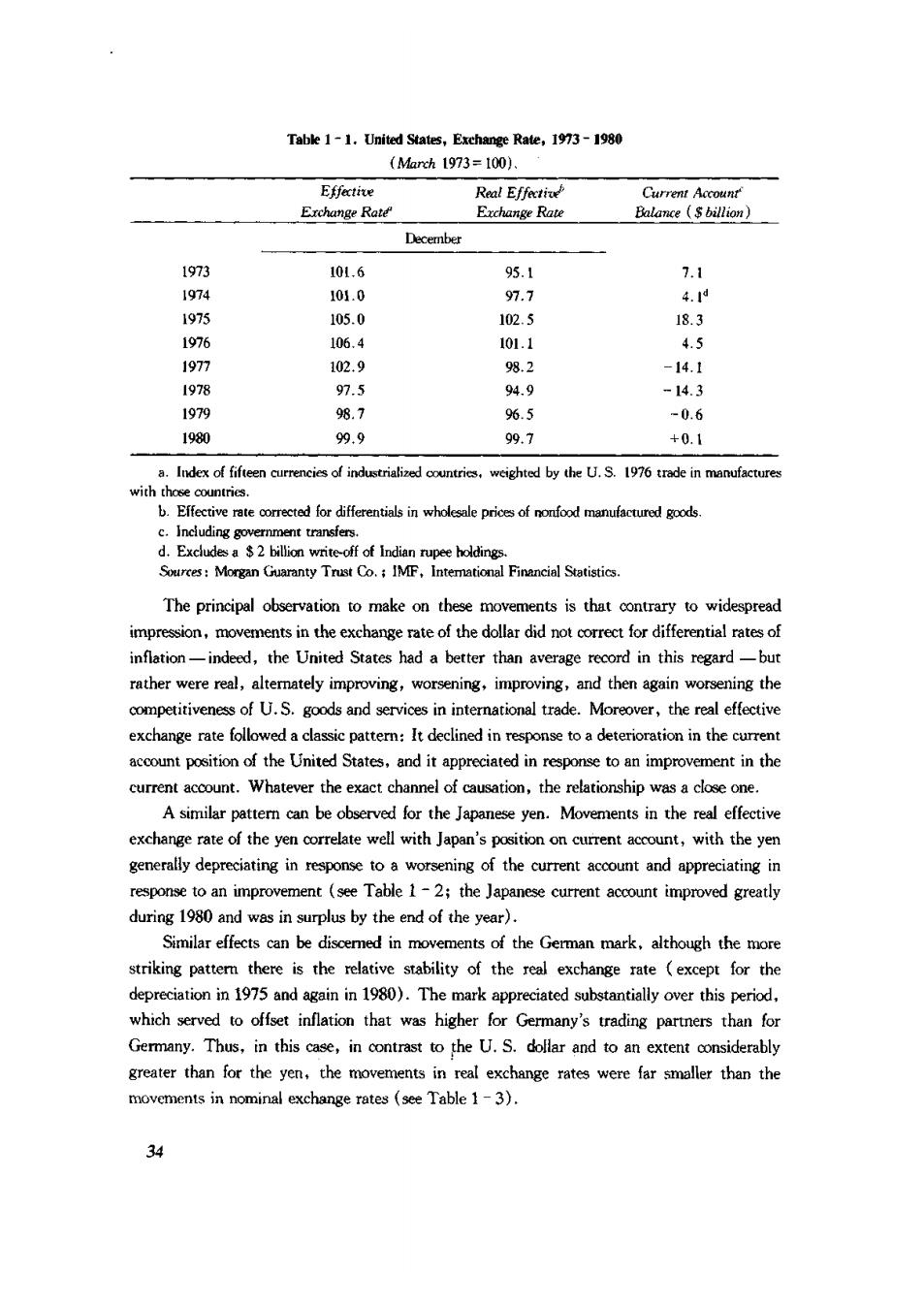

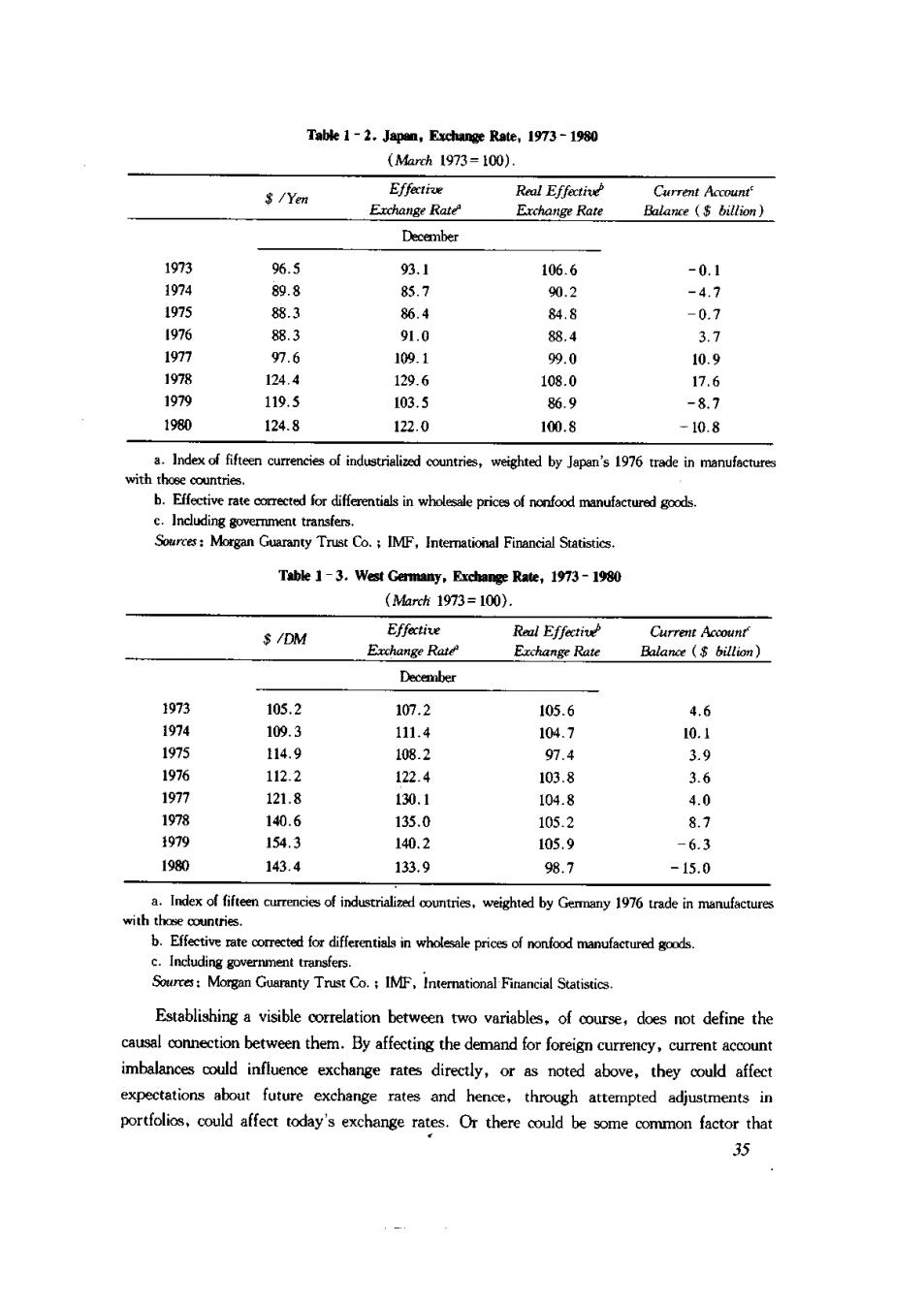

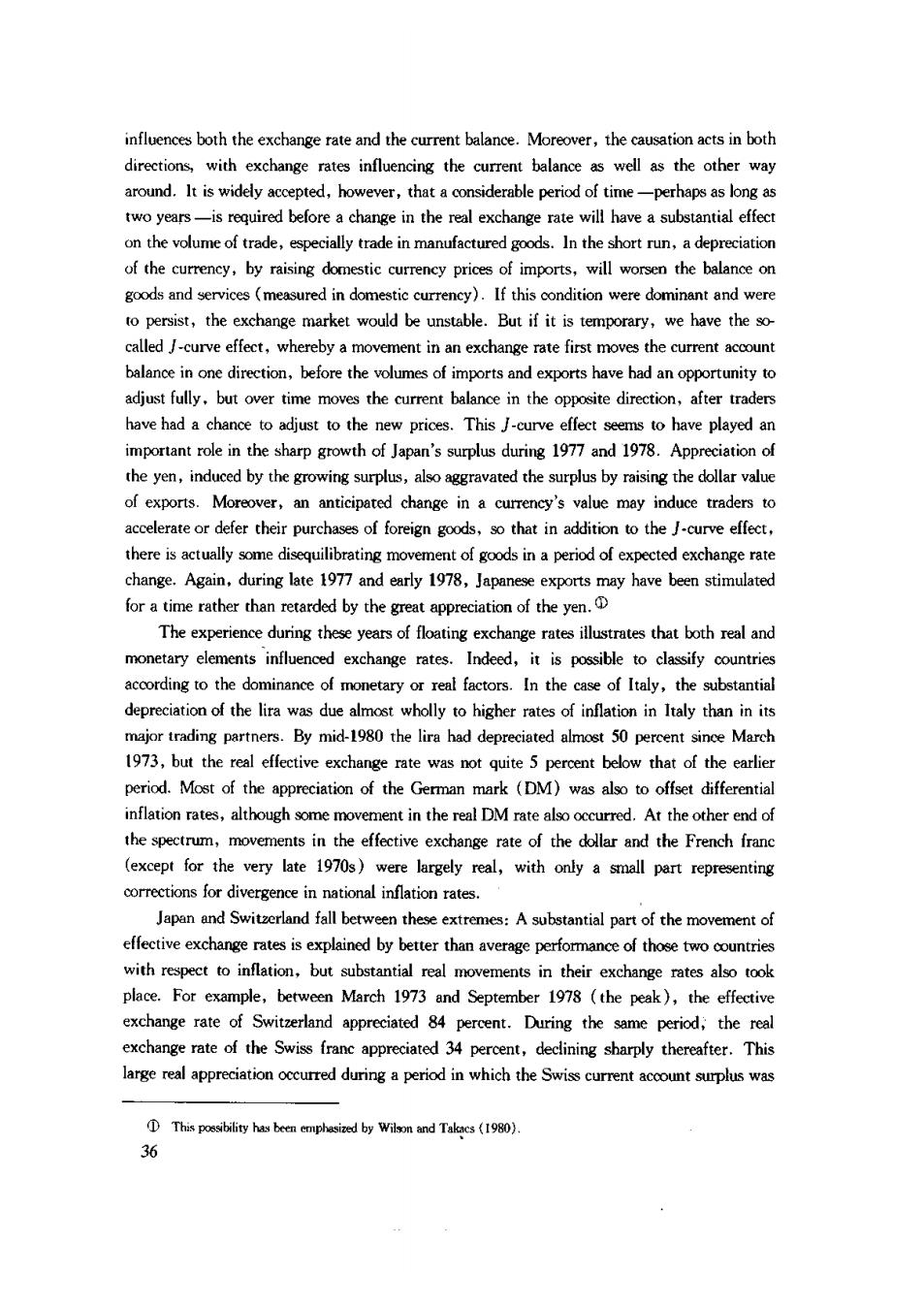

Tabk 1-1.United States,Exchange Rate,1973-1980 (March973=100. Effective Erchange Rate Erchange rate Balance(billion) December 10L.6 051 101. 105.0 102.5 18.3 1976 106.4 101. 4.5 197 102.9 98.2 -14.1 1978 97.5 9H.9 -14.3 1979 98.7 96.5 -0.6 198 99.9 99.7 +0.i Index of fifter with th wcighted by the U.S.1976 trade in manufac b.Effective rate。 ent transfen ces The principal observation to make on these movements is that onary to widespread impression,movements in the exchange rate of the dollar did not correct for differential rates of inflation-indeed,the United States had a better than average record in this regard-but rather were real altemately improving,worsening,improving,and then agair competitiveness of U.S.goods and services in international trade.Moreover,the real effective exchange rate followed a classic patter:It declined the cure the United States.and it in improvement in the current account.Whatever the exact channel of causation.the relationship was a close one. A similar patter can be observed for the Japanese yen.Movements in the real effective change rate of the yen correlate well with Japan's positionon current account,with the yer generally depreciating in response to a worsening of the current account and appreciating in response toan improvement (see Table 1-2;the Japanese current account improved greatly during 1980 and was the end of the year) Similar effects can be discemed in movements of the German mark,although the more striking pattem there is the relative stability of the real exchange rate (except for the depreciation 1975 and again in198).The mark appreciated substantially over this period. which served to offset inflation that was higher for Germany's trading partners than for Germany.Thus,in this case,in contrast to the U.S.dollar and to an extent considerably greater than for the yen,the movements in real exchange rates were far smaller than the movements in nominal exchange rates(see Table 1-3). 34

Table 1-2.Japan,Exchange Rate,1973-1980 (Mah193=100). S/Yen Effectiue Roal Effetie Exchange Rate Exchange Rate Balance (billion) 1973 96.5 93.1 106.6 -0.1 1974 809 85.7 4 1975 81 86.4 84.8 -0.7 1976 88.3 010 88.4 37 197m 076 100 99.0 1978 1244 1306 108.0 176 1070 119.5 103.5 60 1980 124.8 122.0 100.8 -10.8 b.Effective rate ted for differ ntials in wholesale prices of nonfood manufactured goods Including government transfers Sources:Morgan Guaranty Trust Co.IMF,Interational Financial Statistics. Table 1-3.West Germany,Exchange Rate,1973-1980 (Mah1973=100》 $/DM Effective Raul Effectiv Current Acoount Exchange Rate Exchange Kate Balance(billion) Decenber 10s5.2 107.2 105.6 4.6 1974 109.3 111.4 104.7 10.1 1975 114.9 108.2 97.4 3.9 1976 112.2 122.4 103.8 36 1977 121.8 130.1 1048 40 1978 140.6 135.0 1052 87 1979 154.3 140.2 105g -63 1980 143.4 133.9 98.7 -15.0 a.Index of fifteen with th ntries b.Effective ratetordifferetiain whosae pricofondnufacturedd Establishing a visible correlation between two variables,ofouse,does not define the them.By affecting the demnd for foreign influence exchange rates directly,or as noted above,they could affect expectations about future exchange rates and hence,through attempted adjustments in affect today's exchange rates.O there u be that

inf both the exchange rate and the balance.Morever,acts in both directions,with exchange rates influencing the current balance as well as the other way around.It is widely accepted,however,that a considerable period of time- -perhaps as long as wo years-isquired beforea change in the real exchange rate will have a substantial effec on the volume of trade,especially trade in manufactured goods.In the short run,a depreciation of the currency,by raising domestic currency prices of imports,will worsen the balance or (measured in omestic)If ominantand were to persist,the exchange market would be unstable.But if it is temporary,we have the so called J-curve effect,whereby a movement in an exchange rate first moves the current account ,before the voumes of importsand exports have had an opportunityt adjust fully.but over time moves the current balance in the opposite direction,after traders have had a chance to adjust to the new prices.This J-curve effect seems to have played an important role in the sharp growth of Japan's surplus during 1977and 1978. the yen,induced by the growing surplus,also aggravated the surplus by raising the dollar value of exports.Moreover,an anticipated change in a currency's value may induce traders to accelerateor defer their purchasesof foreign goods,so that in addition to the Jcurve effect there is actually some disequilibrating movement of goods in a period of expected exchange rate change.Again,during late 1977 and early 1978,Japanese exports may have been stimulated fora time rather than by the great of the yen. The experience during these years of floating exchange rates illustrates that both real and monetary elements influenced exchange rates.Indeed,it is possible to classify countri according to the dominance of monetary or real factors.In the case of Italy,the substantia depreciation of the lira was due almost wholly to higher rates of inflation in Italy than in its major trading partners.By mid-1980 the lira had depreciated almost 50 per 1973.but the real effective exchange rate was not quite5 percent below that of the earlie period.Most of the appreciation of the German mark (DM)was also to offset differential inflation rates,the cured.At theother r end of thepecrum,movements in the effective exchange rate of the dollar and the French franc (except for the very late 1970s)were largely real,with only a small part representing Japan and Switzerland fall between these extremes:A substantial part of the movement of effective exchange rates is explained by better than average performanceof thse twoounies with,but substantial real movements in their rexchange rates also place.For example,between March 1973 and September 1978 (the peak).the effective exchange rate of Switzerland appreciated 84 percent.During the same period,the real exchangete of the Swiss franc appreciated 34 percent,dedining sharply thereafter.This large real appreciation occurred during a period in which the Swiss current accout surplus was 36