Java Concurrency In Practice 1.1.A (Very)Brief History of Concurrency In the ancient past,computers didn't have operating systems;they executed a single program from beginning to end, and that program had direct access to all the resources of the machine.Not only was it difficult to write programs that ran on the bare metal,but running only a single program at a time was an inefficient use of expensive and scarce computer resources. Operating systems evolved to allow more than one program to run at once,running individual programs in processes: isolated,independently executing programs to which the operating system allocates resources such as memory,file handles,and security credentials.If they needed to,processes could communicate with one another through a variety of coarse-grained communication mechanisms:sockets,signal handlers,shared memory,semaphores,and files. Several motivating factors led to the development of operating systems that allowed multiple programs to execute simultaneously: Resource utilization.Programs sometimes have to wait for external operations such as input or output,and while waiting can do no useful work.It is more efficient to use that wait time to let another program run. Fairness.Multiple users and programs may have equal claims on the machine's resources.It is preferable to let them share the computer via finer-grained time slicing than to let one program run to completion and then start another. Convenience.It is often easier or more desirable to write several programs that each perform a single task and have them coordinate with each other as necessary than to write a single program that performs all the tasks. In early timesharing systems,each process was a virtual von Neumann computer;it had a memory space storing both instructions and data,executing instructions sequentially according to the semantics of the machine language,and interacting with the outside world via the operating system through a set of I/O primitives.For each instruction executed there was a clearly defined "next instruction",and control flowed through the program according to the rules of the instruction set.Nearly all widely used programming languages today follow this sequential programming model, where the language specification clearly defines"what comes next"after a given action is executed. The sequential programming model is intuitive and natural,as it models the way humans work:do one thing at a time, in sequence mostly.Get out of bed,put on your bathrobe,go downstairs and start the tea.As in programming languages,each of these real-world actions is an abstraction for a sequence of finer-grained actions -open the cupboard,select a flavor of tea,measure some tea into the pot,see if there's enough water in the teakettle,if not put some more water in,set it on the stove,turn the stove on,wait for the water to boil,and so on.This last step-waiting for the water to boil-also involves a degree of asynchrony.While the water is heating,you have a choice of what to do- just wait,or do other tasks in that time such as starting the toast (another asynchronous task)or fetching the newspaper,while remaining aware that your attention will soon be needed by the teakettle.The manufacturers of teakettles and toasters know their products are often used in an asynchronous manner,so they raise an audible signal when they complete their task.Finding the right balance of sequentiality and asynchrony is often a characteristic of efficient people-and the same is true of programs. The same concerns(resource utilization,fairness,and convenience)that motivated the development of processes also motivated the development of threads.Threads allow multiple streams of program control flow to coexist within a process.They share process-wide resources such as memory and file handles,but each thread has its own program counter,stack,and local variables.Threads also provide a natural decomposition for exploiting hardware parallelism on multiprocessor systems;multiple threads within the same program can be scheduled simultaneously on multiple CPUs. Threads are sometimes called lightweight processes,and most modern operating systems treat threads,not processes, as the basic units of scheduling.In the absence of explicit coordination,threads execute simultaneously and asynchronously with respect to one another.Since threads share the memory address space of their owning process,all threads within a process have access to the same variables and allocate objects from the same heap,which allows finer- grained data sharing than inter-process mechanisms.But without explicit synchronization to coordinate access to shared data,a thread may modify variables that another thread is in the middle of using,with unpredictable results

2 Java Concurrency In Practice 1.1. A (Very) Brief History of Concurrency In the ancient past, computers didn't have operating systems; they executed a single program from beginning to end, and that program had direct access to all the resources of the machine. Not only was it difficult to write programs that ran on the bare metal, but running only a single program at a time was an inefficient use of expensive and scarce computer resources. Operating systems evolved to allow more than one program to run at once, running individual programs in processes: isolated, independently executing programs to which the operating system allocates resources such as memory, file handles, and security credentials. If they needed to, processes could communicate with one another through a variety of coarseͲgrained communication mechanisms: sockets, signal handlers, shared memory, semaphores, and files. Several motivating factors led to the development of operating systems that allowed multiple programs to execute simultaneously: Resource utilization. Programs sometimes have to wait for external operations such as input or output, and while waiting can do no useful work. It is more efficient to use that wait time to let another program run. Fairness. Multiple users and programs may have equal claims on the machine's resources. It is preferable to let them share the computer via finerͲgrained time slicing than to let one program run to completion and then start another. Convenience. It is often easier or more desirable to write several programs that each perform a single task and have them coordinate with each other as necessary than to write a single program that performs all the tasks. In early timesharing systems, each process was a virtual von Neumann computer; it had a memory space storing both instructions and data, executing instructions sequentially according to the semantics of the machine language, and interacting with the outside world via the operating system through a set of I/O primitives. For each instruction executed there was a clearly defined "next instruction", and control flowed through the program according to the rules of the instruction set. Nearly all widely used programming languages today follow this sequential programming model, where the language specification clearly defines "what comes next" after a given action is executed. The sequential programming model is intuitive and natural, as it models the way humans work: do one thing at a time, in sequence mostly. Get out of bed, put on your bathrobe, go downstairs and start the tea. As in programming languages, each of these realͲworld actions is an abstraction for a sequence of finerͲgrained actions Ͳ open the cupboard, select a flavor of tea, measure some tea into the pot, see if there's enough water in the teakettle, if not put some more water in, set it on the stove, turn the stove on, wait for the water to boil, and so on. This last stepͲwaiting for the water to boilͲalso involves a degree of asynchrony. While the water is heating, you have a choice of what to doͲ just wait, or do other tasks in that time such as starting the toast (another asynchronous task) or fetching the newspaper, while remaining aware that your attention will soon be needed by the teakettle. The manufacturers of teakettles and toasters know their products are often used in an asynchronous manner, so they raise an audible signal when they complete their task. Finding the right balance of sequentiality and asynchrony is often a characteristic of efficient peopleͲand the same is true of programs. The same concerns (resource utilization, fairness, and convenience) that motivated the development of processes also motivated the development of threads. Threads allow multiple streams of program control flow to coexist within a process. They share processͲwide resources such as memory and file handles, but each thread has its own program counter, stack, and local variables. Threads also provide a natural decomposition for exploiting hardware parallelism on multiprocessor systems; multiple threads within the same program can be scheduled simultaneously on multiple CPUs. Threads are sometimes called lightweight processes, and most modern operating systems treat threads, not processes, as the basic units of scheduling. In the absence of explicit coordination, threads execute simultaneously and asynchronously with respect to one another. Since threads share the memory address space of their owning process, all threads within a process have access to the same variables and allocate objects from the same heap, which allows finerͲ grained data sharing than interͲprocess mechanisms. But without explicit synchronization to coordinate access to shared data, a thread may modify variables that another thread is in the middle of using, with unpredictable results.����������

3BChapter 1-Introduction-11B1.2.Benefits of Threads 1.2.Benefits of Threads When used properly,threads can reduce development and maintenance costs and improve the performance of complex applications.Threads make it easier to model how humans work and interact,by turning asynchronous workflows into mostly sequential ones.They can also turn otherwise convoluted code into straight-line code that is easier to write, read,and maintain. Threads are useful in GUl applications for improving the responsiveness of the user interface,and in server applications for improving resource utilization and throughput.They also simplify the implementation of the JVM-the garbage collector usually runs in one or more dedicated threads.Most nontrivial Java applications rely to some degree on threads for their organization. 1.2.1.Exploiting Multiple Processors Multiprocessor systems used to be expensive and rare,found only in large data centers and scientific computing facilities.Today they are cheap and plentiful;even low-end server and midrange desktop systems often have multiple processors.This trend will only accelerate;as it gets harder to scale up clock rates,processor manufacturers will instead put more processor cores on a single chip.All the major chip manufacturers have begun this transition,and we are already seeing machines with dramatically higher processor counts. Since the basic unit of scheduling is the thread,a program with only one thread can run on at most one processor at a time.On a two-processor system,a single-threaded program is giving up access to half the available CPU resources;on a 100-processor system,it is giving up access to 99%.On the other hand,programs with multiple active threads can execute simultaneously on multiple processors.When properly designed,multithreaded programs can improve throughput by utilizing available processor resources more effectively. Using multiple threads can also help achieve better throughput on single-processor systems.If a program is single- threaded,the processor remains idle while it waits for a synchronous l/O operation to complete.In a multithreaded program,another thread can still run while the first thread is waiting for the l/O to complete,allowing the application to still make progress during the blocking I/O.(This is like reading the newspaper while waiting for the water to boil,rather than waiting for the water to boil before starting to read.) 1.2.2.Simplicity of Modeling It is often easier to manage your time when you have only one type of task to perform(fix these twelve bugs)than when you have several(fix the bugs,interview replacement candidates for the system administrator,complete your team's performance evaluations,and create the slides for your presentation next week).When you have only one type of task to do,you can start at the top of the pile and keep working until the pile is exhausted (or you are);you don't have to spend any mental energy figuring out what to work on next.On the other hand,managing multiple priorities and deadlines and switching from task to task usually carries some overhead. The same is true for software:a program that processes one type of task sequentially is simpler to write,less error- prone,and easier to test than one managing multiple different types of tasks at once.Assigning a thread to each type of task or to each element in a simulation affords the illusion of sequentiality and insulates domain logic from the details of scheduling,interleaved operations,asynchronous I/O,and resource waits.A complicated,asynchronous workflow can be decomposed into a number of simpler,synchronous workflows each running in a separate thread,interacting only with each other at specific synchronization points. This benefit is often exploited by frameworks such as servlets or RMI(Remote Method Invocation).The framework handles the details of request management,thread creation,and load balancing,dispatching portions of the request handling to the appropriate application component at the appropriate point in the work-flow.Servlet writers do not need to worry about how many other requests are being processed at the same time or whether the socket input and output streams block;when a servlet's service method is called in response to a web request,it can process the request synchronously as if it were a single-threaded program.This can simplify component development and reduce the learning curve for using such frameworks. 1.2.3.Simplified Handling of Asynchronous Events A server application that accepts socket connections from multiple remote clients may be easier to develop when each connection is allocated its own thread and allowed to use synchronous l/O

3BChapter 1Ͳ IntroductionͲ11B1.2. Benefits of Threads 3 1.2. Benefits of Threads When used properly, threads can reduce development and maintenance costs and improve the performance of complex applications. Threads make it easier to model how humans work and interact, by turning asynchronous workflows into mostly sequential ones. They can also turn otherwise convoluted code into straightͲline code that is easier to write, read, and maintain. Threads are useful in GUI applications for improving the responsiveness of the user interface, and in server applications for improving resource utilization and throughput. They also simplify the implementation of the JVM Ͳthe garbage collector usually runs in one or more dedicated threads. Most nontrivial Java applications rely to some degree on threads for their organization. 1.2.1. Exploiting Multiple Processors Multiprocessor systems used to be expensive and rare, found only in large data centers and scientific computing facilities. Today they are cheap and plentiful; even lowͲend server and midrange desktop systems often have multiple processors. This trend will only accelerate; as it gets harder to scale up clock rates, processor manufacturers will instead put more processor cores on a single chip. All the major chip manufacturers have begun this transition, and we are already seeing machines with dramatically higher processor counts. Since the basic unit of scheduling is the thread, a program with only one thread can run on at most one processor at a time. On a twoͲprocessor system, a singleͲthreaded program is giving up access to half the available CPU resources; on a 100Ͳprocessor system, it is giving up access to 99%. On the other hand, programs with multiple active threads can execute simultaneously on multiple processors. When properly designed, multithreaded programs can improve throughput by utilizing available processor resources more effectively. Using multiple threads can also help achieve better throughput on singleͲprocessor systems. If a program is singleͲ threaded, the processor remains idle while it waits for a synchronous I/O operation to complete. In a multithreaded program, another thread can still run while the first thread is waiting for the I/O to complete, allowing the application to still make progress during the blocking I/O. (This is like reading the newspaper while waiting for the water to boil, rather than waiting for the water to boil before starting to read.) 1.2.2. Simplicity of Modeling It is often easier to manage your time when you have only one type of task to perform (fix these twelve bugs) than when you have several (fix the bugs, interview replacement candidates for the system administrator, complete your team's performance evaluations, and create the slides for your presentation next week). When you have only one type of task to do, you can start at the top of the pile and keep working until the pile is exhausted (or you are); you don't have to spend any mental energy figuring out what to work on next. On the other hand, managing multiple priorities and deadlines and switching from task to task usually carries some overhead. The same is true for software: a program that processes one type of task sequentially is simpler to write, less errorͲ prone, and easier to test than one managing multiple different types of tasks at once. Assigning a thread to each type of task or to each element in a simulation affords the illusion of sequentiality and insulates domain logic from the details of scheduling, interleaved operations, asynchronous I/O, and resource waits. A complicated, asynchronous workflow can be decomposed into a number of simpler, synchronous workflows each running in a separate thread, interacting only with each other at specific synchronization points. This benefit is often exploited by frameworks such as servlets or RMI (Remote Method Invocation). The framework handles the details of request management, thread creation, and load balancing, dispatching portions of the request handling to the appropriate application component at the appropriate point in the workͲflow. Servlet writers do not need to worry about how many other requests are being processed at the same time or whether the socket input and output streams block; when a servlet's service method is called in response to a web request, it can process the request synchronously as if it were a singleͲthreaded program. This can simplify component development and reduce the learning curve for using such frameworks. 1.2.3. Simplified Handling of Asynchronous Events A server application that accepts socket connections from multiple remote clients may be easier to develop when each connection is allocated its own thread and allowed to use synchronous I/O.�����

Java Concurrency In Practice If an application goes to read from a socket when no data is available,read blocks until some data is available.In a single-threaded application,this means that not only does processing the corresponding request stall,but processing of all requests stalls while the single thread is blocked.To avoid this problem,single-threaded server applications are forced to use non-blocking I/O,which is far more complicated and error-prone than synchronous I/O.However,if each request has its own thread,then blocking does not affect the processing of other requests. Historically,operating systems placed relatively low limits on the number of threads that a process could create,as few as several hundred(or even less).As a result,operating systems developed efficient facilities for multiplexed I/O,such as the Unix select and poll system calls,and to access these facilities,the Java class libraries acquired a set of packages (java.nio)for non-blocking I/O.However,operating system support for larger numbers of threads has improved significantly,making the thread-per-client model practical even for large numbers of clients on some platforms. [1]The NPTL threads package,now part of most Linux distributions,was designed to support hundreds of thousands of threads.Non-blocking I/O has its own benefits,but better OS support for threads means that there are fewer situations for which it is essential. 1.2.4.More Responsive User Interfaces GUl applications used to be single-threaded,which meant that you had to either frequently poll throughout the code for input events(which is messy and intrusive)or execute all application code indirectly through a "main event loop".If code called from the main event loop takes too long to execute,the user interface appears to"freeze"until that code finishes,because subsequent user interface events cannot be processed until control is returned to the main event loop. Modern GUl frameworks,such as the AWT and Swing toolkits,replace the main event loop with an event dispatch thread(EDT).When a user interface event such as a button press occurs,application-defined event handlers are called in the event thread.Most GUl frameworks are single-threaded subsystems,so the main event loop is effectively still present,but it runs in its own thread under the control of the GUl toolkit rather than the application. If only short-lived tasks execute in the event thread,the interface remains responsive since the event thread is always able to process user actions reasonably quickly.However,processing a long-running task in the event thread,such as spell-checking a large document or fetching a resource over the network,impairs responsiveness.If the user performs an action while this task is running,there is a long delay before the event thread can process or even acknowledge it.To add insult to injury,not only does the Ul become unresponsive,but it is impossible to cancel the offending task even if the Ul provides a cancel button because the event thread is busy and cannot handle the cancel button-press event until the lengthy task completes!If,however,the long-running task is instead executed in a separate thread,the event thread remains free to process Ul events,making the Ul more responsive

4 Java Concurrency In Practice If an application goes to read from a socket when no data is available, read blocks until some data is available. In a singleͲthreaded application, this means that not only does processing the corresponding request stall, but processing of all requests stalls while the single thread is blocked. To avoid this problem, singleͲthreaded server applications are forced to use nonͲblocking I/O, which is far more complicated and errorͲprone than synchronous I/O. However, if each request has its own thread, then blocking does not affect the processing of other requests. Historically, operating systems placed relatively low limits on the number of threads that a process could create, as few as several hundred (or even less). As a result, operating systems developed efficient facilities for multiplexed I/O, such as the Unix select and poll system calls, and to access these facilities, the Java class libraries acquired a set of packages (java.nio) for nonͲblocking I/O. However, operating system support for larger numbers of threads has improved significantly, making the threadͲperͲclient model practical even for large numbers of clients on some platforms.[1] [1] The NPTL threads package, now part of most Linux distributions, was designed to support hundreds of thousands of threads. NonͲblocking I/O has its own benefits, but better OS support for threads means that there are fewer situations for which it is essential. 1.2.4. More Responsive User Interfaces GUI applications used to be singleͲthreaded, which meant that you had to either frequently poll throughout the code for input events (which is messy and intrusive) or execute all application code indirectly through a "main event loop". If code called from the main event loop takes too long to execute, the user interface appears to "freeze" until that code finishes, because subsequent user interface events cannot be processed until control is returned to the main event loop. Modern GUI frameworks, such as the AWT and Swing toolkits, replace the main event loop with an event dispatch thread (EDT). When a user interface event such as a button press occurs, applicationͲdefined event handlers are called in the event thread. Most GUI frameworks are singleͲthreaded subsystems, so the main event loop is effectively still present, but it runs in its own thread under the control of the GUI toolkit rather than the application. If only shortͲlived tasks execute in the event thread, the interface remains responsive since the event thread is always able to process user actions reasonably quickly. However, processing a longͲrunning task in the event thread, such as spellͲchecking a large document or fetching a resource over the network, impairs responsiveness. If the user performs an action while this task is running, there is a long delay before the event thread can process or even acknowledge it. To add insult to injury, not only does the UI become unresponsive, but it is impossible to cancel the offending task even if the UI provides a cancel button because the event thread is busy and cannot handle the cancel buttonͲpress event until the lengthy task completes! If, however, the longͲrunning task is instead executed in a separate thread, the event thread remains free to process UI events, making the UI more responsive

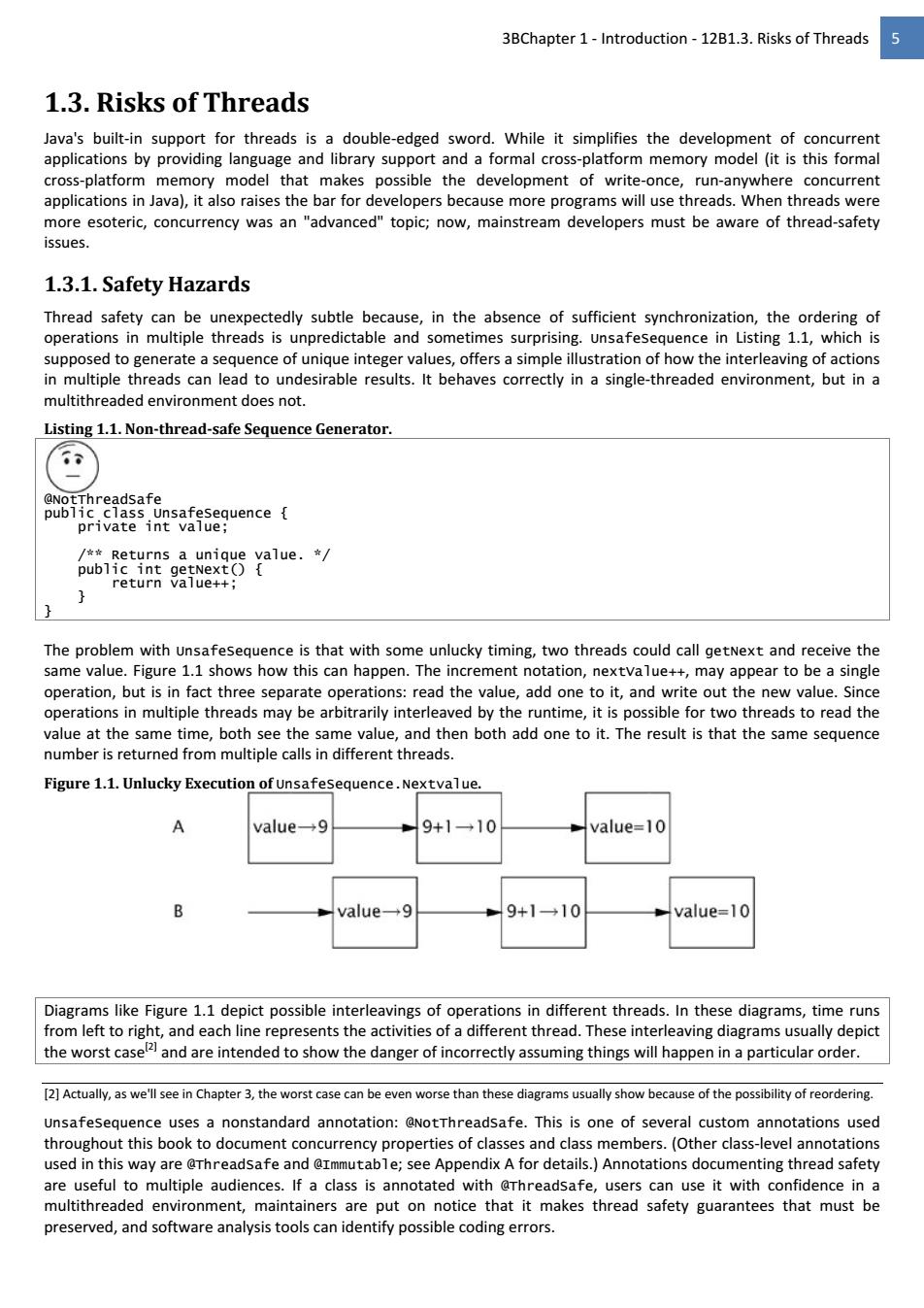

3BChapter 1-Introduction-12B1.3.Risks of Threads 5 1.3.Risks of Threads Java's built-in support for threads is a double-edged sword.While it simplifies the development of concurrent applications by providing language and library support and a formal cross-platform memory model(it is this formal cross-platform memory model that makes possible the development of write-once,run-anywhere concurrent applications in Java),it also raises the bar for developers because more programs will use threads.When threads were more esoteric,concurrency was an "advanced"topic;now,mainstream developers must be aware of thread-safety issues. 1.3.1.Safety Hazards Thread safety can be unexpectedly subtle because,in the absence of sufficient synchronization,the ordering of operations in multiple threads is unpredictable and sometimes surprising.Unsafesequence in Listing 1.1,which is supposed to generate a sequence of unique integer values,offers a simple illustration of how the interleaving of actions in multiple threads can lead to undesirable results.It behaves correctly in a single-threaded environment,but in a multithreaded environment does not. Listing 1.1.Non-thread-safe Sequence Generator. @NotThreadsafe public class Unsafesequence private int value; /*Returns a unique value.* public int getNext(){ return value++; The problem with Unsafesequence is that with some unlucky timing,two threads could call getNext and receive the same value.Figure 1.1 shows how this can happen.The increment notation,nextvalue++,may appear to be a single operation,but is in fact three separate operations:read the value,add one to it,and write out the new value.Since operations in multiple threads may be arbitrarily interleaved by the runtime,it is possible for two threads to read the value at the same time,both see the same value,and then both add one to it.The result is that the same sequence number is returned from multiple calls in different threads. Figure 1.1.Unlucky Execution of Unsafesequence.Nextvalue. value→9 9+1→10 value=10 value→9 9+1→10 value=10 Diagrams like Figure 1.1 depict possible interleavings of operations in different threads.In these diagrams,time runs from left to right,and each line represents the activities of a different thread.These interleaving diagrams usually depict the worst casel2 and are intended to show the danger of incorrectly assuming things will happen in a particular order. [2]Actually,as we'll see in Chapter 3,the worst case can be even worse than these diagrams usually show because of the possibility of reordering. Unsafesequence uses a nonstandard annotation:@NotThreadsafe.This is one of several custom annotations used throughout this book to document concurrency properties of classes and class members.(Other class-level annotations used in this way are @Threadsafe and @Immutable;see Appendix A for details.)Annotations documenting thread safety are useful to multiple audiences.If a class is annotated with @rhreadsafe,users can use it with confidence in a multithreaded environment,maintainers are put on notice that it makes thread safety guarantees that must be preserved,and software analysis tools can identify possible coding errors

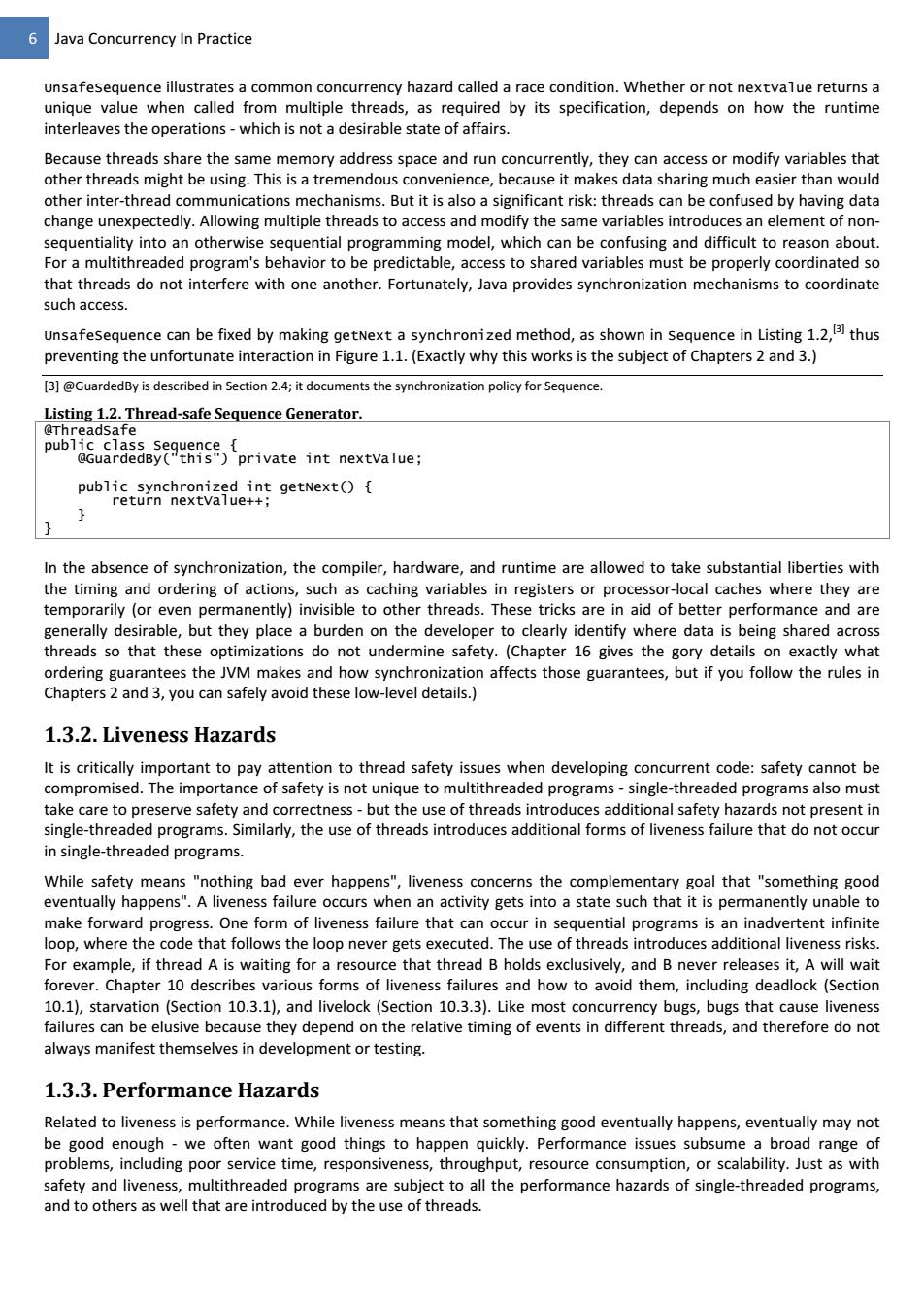

3BChapter 1Ͳ IntroductionͲ12B1.3. Risks of Threads 5 1.3. Risks of Threads Java's builtͲin support for threads is a doubleͲedged sword. While it simplifies the development of concurrent applications by providing language and library support and a formal crossͲplatform memory model (it is this formal crossͲplatform memory model that makes possible the development of writeͲonce, runͲanywhere concurrent applications in Java), it also raises the bar for developers because more programs will use threads. When threads were more esoteric, concurrency was an "advanced" topic; now, mainstream developers must be aware of threadͲsafety issues. 1.3.1. Safety Hazards Thread safety can be unexpectedly subtle because, in the absence of sufficient synchronization, the ordering of operations in multiple threads is unpredictable and sometimes surprising. UnsafeSequence in Listing 1.1, which is supposed to generate a sequence of unique integer values, offers a simple illustration of how the interleaving of actions in multiple threads can lead to undesirable results. It behaves correctly in a singleͲthreaded environment, but in a multithreaded environment does not. Listing 1.1. NonǦthreadǦsafe Sequence Generator. @NotThreadSafe public class UnsafeSequence { private int value; /** Returns a unique value. */ public int getNext() { return value++; } } The problem with UnsafeSequence is that with some unlucky timing, two threads could call getNext and receive the same value. Figure 1.1 shows how this can happen. The increment notation, nextValue++, may appear to be a single operation, but is in fact three separate operations: read the value, add one to it, and write out the new value. Since operations in multiple threads may be arbitrarily interleaved by the runtime, it is possible for two threads to read the value at the same time, both see the same value, and then both add one to it. The result is that the same sequence number is returned from multiple calls in different threads. Figure 1.1. Unlucky Execution of UnsafeSequence.Nextvalue. Diagrams like Figure 1.1 depict possible interleavings of operations in different threads. In these diagrams, time runs from left to right, and each line represents the activities of a different thread. These interleaving diagrams usually depict the worst case[2] and are intended to show the danger of incorrectly assuming things will happen in a particular order. [2] Actually, as we'll see in Chapter 3, the worst case can be even worse than these diagrams usually show because of the possibility of reordering. UnsafeSequence uses a nonstandard annotation: @NotThreadSafe. This is one of several custom annotations used throughout this book to document concurrency properties of classes and class members. (Other classͲlevel annotations used in this way are @ThreadSafe and @Immutable; see Appendix A for details.) Annotations documenting thread safety are useful to multiple audiences. If a class is annotated with @ThreadSafe, users can use it with confidence in a multithreaded environment, maintainers are put on notice that it makes thread safety guarantees that must be preserved, and software analysis tools can identify possible coding errors.���

6 Java Concurrency In Practice Unsafesequence illustrates a common concurrency hazard called a race condition.Whether or not nextvalue returns a unique value when called from multiple threads,as required by its specification,depends on how the runtime interleaves the operations-which is not a desirable state of affairs. Because threads share the same memory address space and run concurrently,they can access or modify variables that other threads might be using.This is a tremendous convenience,because it makes data sharing much easier than would other inter-thread communications mechanisms.But it is also a significant risk:threads can be confused by having data change unexpectedly.Allowing multiple threads to access and modify the same variables introduces an element of non- sequentiality into an otherwise sequential programming model,which can be confusing and difficult to reason about. For a multithreaded program's behavior to be predictable,access to shared variables must be properly coordinated so that threads do not interfere with one another.Fortunately,Java provides synchronization mechanisms to coordinate such access. unsafesequence can be fixed by making getNext a synchronized method,as shown in sequence in Listing 1.2,13 thus preventing the unfortunate interaction in Figure 1.1.(Exactly why this works is the subject of Chapters 2 and 3.) [3]@GuardedBy is described in Section 2.4;it documents the synchronization policy for Sequence. Listing 1.2.Thread-safe Sequence Generator. @Threadsafe public class seguence @GuardedBy("this")private int nextvalue; public synchronized int getNext(){ return nextvalue++; In the absence of synchronization,the compiler,hardware,and runtime are allowed to take substantial liberties with the timing and ordering of actions,such as caching variables in registers or processor-local caches where they are temporarily (or even permanently)invisible to other threads.These tricks are in aid of better performance and are generally desirable,but they place a burden on the developer to clearly identify where data is being shared across threads so that these optimizations do not undermine safety.(Chapter 16 gives the gory details on exactly what ordering guarantees the JVM makes and how synchronization affects those guarantees,but if you follow the rules in Chapters 2 and 3,you can safely avoid these low-level details.) 1.3.2.Liveness Hazards It is critically important to pay attention to thread safety issues when developing concurrent code:safety cannot be compromised.The importance of safety is not unique to multithreaded programs-single-threaded programs also must take care to preserve safety and correctness-but the use of threads introduces additional safety hazards not present in single-threaded programs.Similarly,the use of threads introduces additional forms of liveness failure that do not occur in single-threaded programs. While safety means "nothing bad ever happens",liveness concerns the complementary goal that "something good eventually happens".A liveness failure occurs when an activity gets into a state such that it is permanently unable to make forward progress.One form of liveness failure that can occur in sequential programs is an inadvertent infinite loop,where the code that follows the loop never gets executed.The use of threads introduces additional liveness risks. For example,if thread A is waiting for a resource that thread B holds exclusively,and B never releases it,A will wait forever.Chapter 10 describes various forms of liveness failures and how to avoid them,including deadlock(Section 10.1),starvation (Section 10.3.1),and livelock(Section 10.3.3).Like most concurrency bugs,bugs that cause liveness failures can be elusive because they depend on the relative timing of events in different threads,and therefore do not always manifest themselves in development or testing. 1.3.3.Performance Hazards Related to liveness is performance.While liveness means that something good eventually happens,eventually may not be good enough-we often want good things to happen quickly.Performance issues subsume a broad range of problems,including poor service time,responsiveness,throughput,resource consumption,or scalability.Just as with safety and liveness,multithreaded programs are subject to all the performance hazards of single-threaded programs, and to others as well that are introduced by the use of threads

6 Java Concurrency In Practice UnsafeSequence illustrates a common concurrency hazard called a race condition. Whether or not nextValue returns a unique value when called from multiple threads, as required by its specification, depends on how the runtime interleaves the operationsͲwhich is not a desirable state of affairs. Because threads share the same memory address space and run concurrently, they can access or modify variables that other threads might be using. This is a tremendous convenience, because it makes data sharing much easier than would other interͲthread communications mechanisms. But it is also a significant risk: threads can be confused by having data change unexpectedly. Allowing multiple threads to access and modify the same variables introduces an element of nonͲ sequentiality into an otherwise sequential programming model, which can be confusing and difficult to reason about. For a multithreaded program's behavior to be predictable, access to shared variables must be properly coordinated so that threads do not interfere with one another. Fortunately, Java provides synchronization mechanisms to coordinate such access. UnsafeSequence can be fixed by making getNext a synchronized method, as shown in Sequence in Listing 1.2,[3] thus preventing the unfortunate interaction in Figure 1.1. (Exactly why this works is the subject of Chapters 2 and 3.) [3] @GuardedBy is described in Section 2.4; it documents the synchronization policy for Sequence. Listing 1.2. ThreadǦsafe Sequence Generator. @ThreadSafe public class Sequence { @GuardedBy("this") private int nextValue; public synchronized int getNext() { return nextValue++; } } In the absence of synchronization, the compiler, hardware, and runtime are allowed to take substantial liberties with the timing and ordering of actions, such as caching variables in registers or processorͲlocal caches where they are temporarily (or even permanently) invisible to other threads. These tricks are in aid of better performance and are generally desirable, but they place a burden on the developer to clearly identify where data is being shared across threads so that these optimizations do not undermine safety. (Chapter 16 gives the gory details on exactly what ordering guarantees the JVM makes and how synchronization affects those guarantees, but if you follow the rules in Chapters 2 and 3, you can safely avoid these lowͲlevel details.) 1.3.2. Liveness Hazards It is critically important to pay attention to thread safety issues when developing concurrent code: safety cannot be compromised. The importance of safety is not unique to multithreaded programsͲsingleͲthreaded programs also must take care to preserve safety and correctnessͲbut the use of threads introduces additional safety hazards not present in singleͲthreaded programs. Similarly, the use of threads introduces additional forms of liveness failure that do not occur in singleͲthreaded programs. While safety means "nothing bad ever happens", liveness concerns the complementary goal that "something good eventually happens". A liveness failure occurs when an activity gets into a state such that it is permanently unable to make forward progress. One form of liveness failure that can occur in sequential programs is an inadvertent infinite loop, where the code that follows the loop never gets executed. The use of threads introduces additional liveness risks. For example, if thread A is waiting for a resource that thread B holds exclusively, and B never releases it, A will wait forever. Chapter 10 describes various forms of liveness failures and how to avoid them, including deadlock (Section 10.1), starvation (Section 10.3.1), and livelock (Section 10.3.3). Like most concurrency bugs, bugs that cause liveness failures can be elusive because they depend on the relative timing of events in different threads, and therefore do not always manifest themselves in development or testing. 1.3.3. Performance Hazards Related to liveness is performance. While liveness means that something good eventually happens, eventually may not be good enough Ͳ we often want good things to happen quickly. Performance issues subsume a broad range of problems, including poor service time, responsiveness, throughput, resource consumption, or scalability. Just as with safety and liveness, multithreaded programs are subject to all the performance hazards of singleͲthreaded programs, and to others as well that are introduced by the use of threads.��������