xiv Contents 7.1.3 Isoflavones .195 7.1.4 Flavones.. ..196 71 5 Flavonols .197 7.1.6 Leucoanthocyanidins and Flavan-4-ols. .198 7.1.7 Anthocyanin. .200 7.1.8 Hydroxylated Flavonoids from E.coli Expressing Plant P450s. 202 7.2 Microbial Metabolism of Flavonoids. 206 72 1 Chalcones 207 72 2 Flavanones 209 72 3 Isoflavones 214 724 Flavones. 218 72 5 Flavonols 72 6 Catechins ))1 7.2.7 Anthocyanins ))A )20 )17 Refere 238 8.Biosynthesis and Manipulation of Flavonoids in Forage Legumes .257 n 8.1 Introduction 257 11D 058 12 8.1.3 Flay 82 ynthe of Fla synth ocyanir y 825 osynt sis of egume methyla d 82.6 synth kins and No 8.3 nipulation of Flavonoids in Legumes 268 Manipulation of ins in Legumes. 204 8.32 Proanthocyanid Manipulation of Isoflavonoids in Legumes. 270 8.4 Conclusions. 2 References. .272 9.Anthocyanins as Food Colorants. 283 Nuno Mateus and Victor de Freitas 9.1 Introduction. 283 9.2 Anthocyanins as a Food Colorant. .284 9.3 Anthocyanins:Structure and Natural Sources 285 9.4 Extraction and Analysis of Anthocyanins. 287 9.5 Anthocyanin Stability and Equilibrium Forms 287 9.6 Anthocyanin Extracts and Applications.. 290

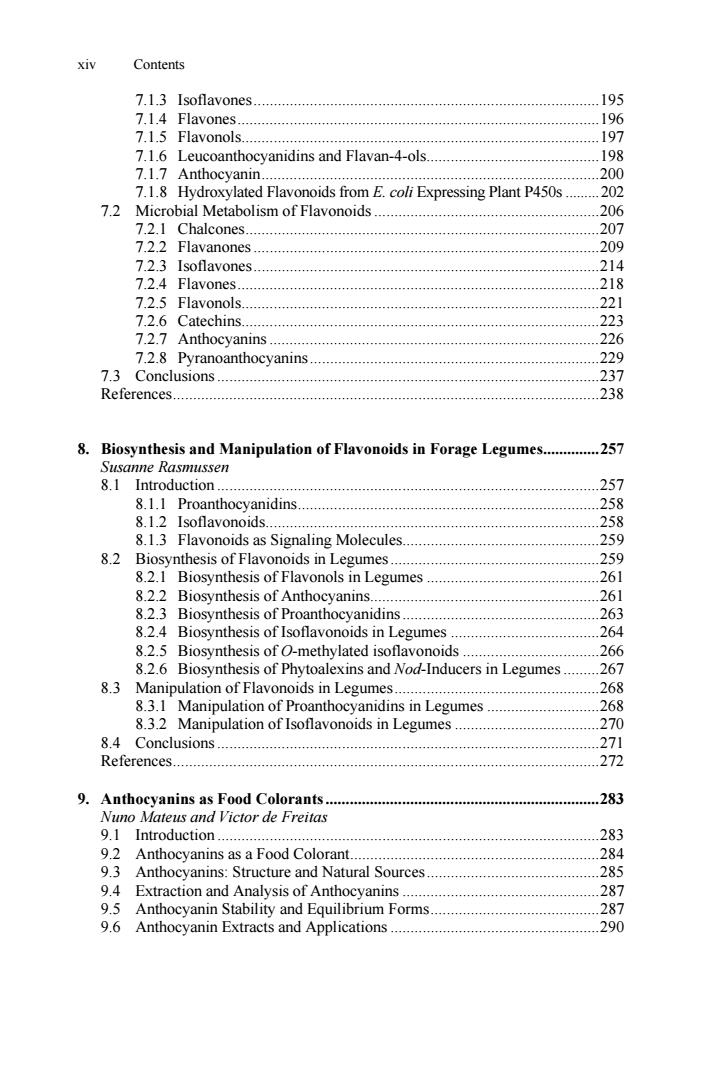

xiv Contents 7.1.3 Isoflavones......................................................................................195 7.1.4 Flavones..........................................................................................196 7.1.5 Flavonols.........................................................................................197 7.1.6 Leucoanthocyanidins and Flavan-4-ols...........................................198 7.1.7 Anthocyanin....................................................................................200 7.1.8 Hydroxylated Flavonoids from E. coli Expressing Plant P450s .........202 7.2 Microbial Metabolism of Flavonoids ........................................................206 7.2.1 Chalcones........................................................................................207 7.2.2 Flavanones ......................................................................................209 7.2.3 Isoflavones......................................................................................214 7.2.4 Flavones..........................................................................................218 7.2.5 Flavonols.........................................................................................221 7.2.6 Catechins.........................................................................................223 7.2.7 Anthocyanins ..................................................................................226 7.2.8 Pyranoanthocyanins........................................................................229 7.3 Conclusions ...............................................................................................237 References..........................................................................................................238 8. Biosynthesis and Manipulation of Flavonoids in Forage Legumes..............257 Susanne Rasmussen 8.1 Introduction ...............................................................................................257 8.1.1 Proanthocyanidins...........................................................................258 8.1.2 Isoflavonoids...................................................................................258 8.1.3 Flavonoids as Signaling Molecules.................................................259 8.2 Biosynthesis of Flavonoids in Legumes....................................................259 8.2.1 Biosynthesis of Flavonols in Legumes ...........................................261 8.2.2 Biosynthesis of Anthocyanins.........................................................261 8.2.3 Biosynthesis of Proanthocyanidins .................................................263 8.2.4 Biosynthesis of Isoflavonoids in Legumes .....................................264 8.2.5 Biosynthesis of O-methylated isoflavonoids ..................................266 8.2.6 Biosynthesis of Phytoalexins and Nod-Inducers in Legumes .........267 8.3 Manipulation of Flavonoids in Legumes...................................................268 8.3.1 Manipulation of Proanthocyanidins in Legumes ............................268 8.3.2 Manipulation of Isoflavonoids in Legumes ....................................270 8.4 Conclusions ...............................................................................................271 References..........................................................................................................272 9. Anthocyanins as Food Colorants ....................................................................283 Nuno Mateus and Victor de Freitas 9.1 Introduction ...............................................................................................283 9.2 Anthocyanins as a Food Colorant..............................................................284 9.3 Anthocyanins: Structure and Natural Sources...........................................285 9.4 Extraction and Analysis of Anthocyanins .................................................287 9.5 Anthocyanin Stability and Equilibrium Forms..........................................287 9.6 Anthocyanin Extracts and Applications ....................................................290

Contents nents:New Colors 291 ortisins:New Blue Anth Future Perspectives for the Food Industrd Foo Colorans Acknowledgments. 298 References.. 298 10.Interactions Between Flavonoids that Benefit Human Health.... 305 Mary Ann Lila 10.1 Phytochemical Interactions.. .305 10.2 Why Are Multiple Bioactive Phytochemicals Usually Involved?. .308 10.3 Flavonoid Interactions that Potentiate Biological Activity.. 309 10.4 In Vitro Investigations of Flavonoid Interactions... 313 10.5 Conclusion/Opportunities for Future Research. 319 Acknowledgements. 320 References. .320 Index. 325

Contents xv 9.7 Anthocyanins and Derived Pigments: New Colors ...................................291 9.7.1 Portisins: New Blue Anthocyanin-Derived Food Colorants? .........294 9.8 Future Perspectives for the Food Industry.................................................297 Acknowledgments..............................................................................................298 References..........................................................................................................298 10. Interactions Between Flavonoids that Benefit Human Health.....................305 Mary Ann Lila 10.1 Phytochemical Interactions........................................................................305 10.2 Why Are Multiple Bioactive Phytochemicals Usually Involved?..............308 10.3 Flavonoid Interactions that Potentiate Biological Activity........................309 10.4 In Vitro Investigations of Flavonoid Interactions......................................313 10.5 Conclusion/Opportunities for Future Research .........................................319 Acknowledgements............................................................................................320 References..........................................................................................................320 Index .......................................................................................................................325

Contributors Joseph A.Chemler State University of New York at Buffalo,Chemical and Biological Engineering, jchemler@buffalo.edu Kevin M.Davies New Zealand Institute for Crop Food Research Ltd,Private Bag 11600, Palmerston North,New Zealand, daviesk@crop.cri.nz Victor de Freitas Department of Chemistry,University of Porto,CIQ,Rua do Campo Alegre,687, 4169-007 Porto,Portugal vfreitas@fc.up.pt Simon Deroles New Zealand Institute for Crop&Food Research Ltd,Private Bag 11600. Palmerston north new zealand deroless@crop.cri.nz Kevin S Gould School of Biolo ical Scier PO.Box 600,Wellingt es,Victoria University of Wellington n,New Zealand, kevin.gould@vuw.ac.nz es B.Hatie S Re ences,Uni ds Re esearch Centre,Tennent Drive Private E Bag 11008,Palm erston North,New Zealand. Jimmy.hatier(@agresearch.co.nz

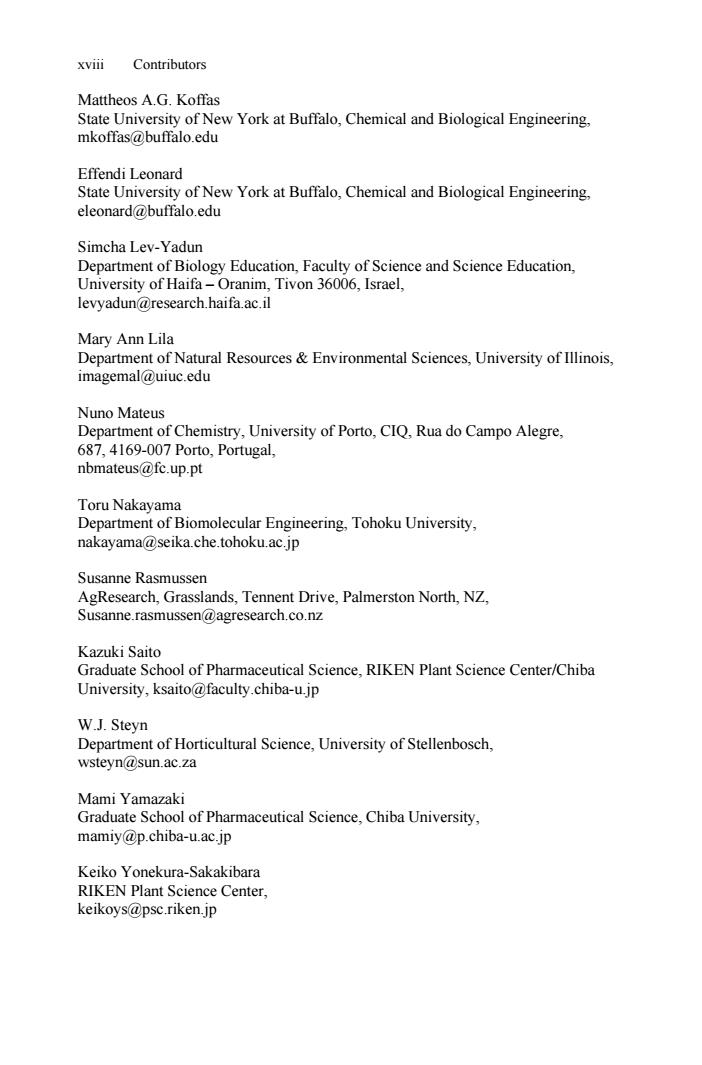

Contributors Joseph A. Chemler State University of New York at Buffalo, Chemical and Biological Engineering, jchemler@buffalo.edu Kevin M. Davies New Zealand Institute for Crop & Food Research Ltd, Private Bag 11600, Palmerston North, New Zealand, daviesk@crop.cri.nz Victor de Freitas Department of Chemistry, University of Porto, CIQ, Rua do Campo Alegre, 687, 4169-007 Porto, Portugal, vfreitas@fc.up.pt Simon Deroles New Zealand Institute for Crop & Food Research Ltd, Private Bag 11600, Palmerston North, New Zealand, deroless@crop.cri.nz Kevin S. Gould School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University of Wellington, P.O. Box 600, Wellington, New Zealand, kevin.gould@vuw.ac.nz Jean-Hugues B. Hatier School of Biological Sciences, University of Auckland, Auckland. Current address: AgResearch Limited, Grasslands Research Centre, Tennent Drive, Private Bag 11008, Palmerston North, New Zealand, jimmy.hatier@agresearch.co.nz

Contributors Mattheos A.G.Koffas State Ur offas o New York at Buttalo,Chemical and Biological Engineering. Effendi Leonard State University of New York at Buffalo,Chemical and Biological Engineering. eleonard@buffalo.edu Simcha Lev-Yadun Department of Biology Education,Faculty of Science and Science Education, University of Haifa-Oranim,Tivon 36006,Israel, levyadun@research.haifa.ac.il Mary Ann Lila Department of Natural Resources&Environmental Sciences,University of Illinois, imagemal@uiuc.edu Nuno mateus Department of Chemistry,University of Porto,CIQ.Rua do Campo Alegre, 687,4169-007 Porto,Portugal, nbmateus @fc.up.pt Toru Nakayama Department of Biomolecular Engineering.Tohoku University, nakayama@seika.che.tohoku.ac.jp susanne Rasmussen AgResearch,Grasslands,Tennent Drive,Palmerston North,NZ usanne.rasmussen@agresearch.co.nz Kazuki Saito Graduate S hool of Pharmaceutical Science,RIKEN Plant Science Center/Chiba University.ksaito@faculty.chiba-u.jp W.J.Stey Departm ent of Horticultural Science,University of Stellenbosch wsteyn@sun.ac.za Mami Yamazaki Graduate S l of Pharmaceutical Science,Chiba University, mamiy@p.chiba-u.ac.jp Keiko Yonekura-Sakakibara RIKEN Plant Science Center keikoys@psc.riken.jp

xviii Contributors Mattheos A.G. Koffas State University of New York at Buffalo, Chemical and Biological Engineering, mkoffas@buffalo.edu Effendi Leonard State University of New York at Buffalo, Chemical and Biological Engineering, eleonard@buffalo.edu Simcha Lev-Yadun Department of Biology Education, Faculty of Science and Science Education, University of Haifa – Oranim, Tivon 36006, Israel, levyadun@research.haifa.ac.il Mary Ann Lila Department of Natural Resources & Environmental Sciences, University of Illinois, imagemal@uiuc.edu Nuno Mateus Department of Chemistry, University of Porto, CIQ, Rua do Campo Alegre, 687, 4169-007 Porto, Portugal, nbmateus@fc.up.pt Toru Nakayama Department of Biomolecular Engineering, Tohoku University, nakayama@seika.che.tohoku.ac.jp Susanne Rasmussen AgResearch, Grasslands, Tennent Drive, Palmerston North, NZ, Susanne.rasmussen@agresearch.co.nz Kazuki Saito Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Science, RIKEN Plant Science Center/Chiba University, ksaito@faculty.chiba-u.jp W.J. Steyn Department of Horticultural Science, University of Stellenbosch, wsteyn@sun.ac.za Mami Yamazaki Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Science, Chiba University, mamiy@p.chiba-u.ac.jp Keiko Yonekura-Sakakibara RIKEN Plant Science Center, keikoys@psc.riken.jp

1 Anthocyanin Function in Vegetative Organs Jean-Hugues B.Hatier'and Kevin S.Gould2 ch.co.n dCuwrettpgio8 a agres 2School of Biological Sciences,Victoria University of Wellington,P.O.Box 600.Wellington New Zealand.kevin gould@vuw ac.nz Abstract.Possible function s of anthe nins in le roots and other v organs have lon attracted scientific debate Key functional hpotheses include (i protection of chloroplasts from the adverse effects of excess light,(ii)attenuation of UV-B radiation;and ()antioxidant actr vity.However,recent data indicate that the degree to which each of th production.Wes est instead that anthoc nins r modulators of reactive oxygen signalling cascades involved in plant growth and development. responses to stress,and gene expression. 1.1 Introduction "Yet it is difficult to find a hypothesis which would fit all cases of anthocyanin on w out red h uction to abs The pigment is produced.of und to take place.For the time being y that it has no been satisfactorily determined in any one case whether its development is either an advantage or a disadvantage to the plant" From Muriel Wheldale's The Anthocyanin Pigments of Plants,1916 The possible physiological roles of anth ocyanins in vegetative ti sues have perplexed l over a century Anthocyani dre to acuoles o al,ground and vascular organs They occu in roots,both subterran and aerial,and in hypocotyls coleoptile stems,tubers,rhizomes,stolons,bulbs,corms,phylloclades,axillary buds,and leaves There are red vegetative organs in plants from all terrestrial biomes,from the basal liverworts to the most advanced angiosperms. Plants alsc show tremendous diversity in anthocyanin expression.In leaves,for example K.Gould et al.(eds.),Anthocyanins,DOI:10.1007/978-0-387-77335-3_1, Springer Science+Business Media,LLC 2009

1 Anthocyanin Function in Vegetative Organs Abstract. Possible functions of anthocyanins in leaves, stems, roots and other vegetative organs have long attracted scientific debate. Key functional hypotheses include: (i) protection of chloroplasts from the adverse effects of excess light; (ii) attenuation of UV-B radiation; and (iii) antioxidant activity. However, recent data indicate that the degree to which each of these processes is affected by anthocyanins varies greatly across plant species. Indeed, none of the hypotheses adequately explains variation in spatial and temporal patterns of anthocyanin production. We suggest instead that anthocyanins may have a more indirect role, as modulators of reactive oxygen signalling cascades involved in plant growth and development, responses to stress, and gene expression. 1.1 Introduction From Muriel Wheldale’s The Anthocyanin Pigments of Plants, 1916. The possible physiological roles of anthocyanins in vegetative tissues have perplexed scientists for well over a century. Anthocyanins are to be found in the vacuoles of almost every cell type in the epidermal, ground, and vascular tissues of all vegetative organs. They occur in roots, both subterranean and aerial, and in hypocotyls, coleoptiles, stems, tubers, rhizomes, stolons, bulbs, corms, phylloclades, axillary buds, and leaves. There are red vegetative organs in plants from all terrestrial biomes, from the basal liverworts to the most advanced angiosperms. Plants also show tremendous diversity in anthocyanin expression. In leaves, for example, K. Gould et al. (eds.), Anthocyanins, DOI: 10.1007/978-0-387-77335-3_1, © Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2009 Jean-Hugues B. Hatier1 and Kevin S. Gould2 1 School of Biological Sciences, University of Auckland, Auckland. Current address: AgResearch Limited, Grasslands Research Centre, Tennent Drive, Private Bag 11008, Palmerston North, New Zealand, jimmy.hatier@agresearch.co.nz 2 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University of Wellington, P.O. Box 600, Wellington, New Zealand, kevin.gould@vuw.ac.nz “Yet it is difficult to find a hypothesis which would fit all cases of anthocyanin distribution without reduction to absurdity. The pigment is produced, of necessity, in tissues where the conditions are such that the chemical reactions leading to anthocyanin formation are bound to take place. For the time being we may safely say that it has not been satisfactorily determined in any one case whether its development is either an advantage or a disadvantage to the plant