40 The Journal of Finance return according to his beliefs.Different investors hold different beliefs about various arbitrageurs'abilities,so one arbitrageur does not end up with all the funds.The market share of each arbitrageur is just the total fraction of investors who believe that he has the highest expected return.The total share of money allocated to a given segment is just the sum of these market shares across all arbitrageurs in the segment.Importantly,we assume that arbitra- geurs across many segments have,on average,earned high enough returns to convince investors to invest with them rather than to index.1 The key remaining question is how investors update their beliefs about the future expected returns of an arbitrageur.We assume that investors have no information about the structure of the model-determining asset prices in any segment.In particular,they do not know the trading strategy employed by any arbitrageur.This assumption is meant to capture the idea that arbitrage strategies are difficult to understand,and a lot of specialized knowledge is needed for investors to evaluate them.In part,this is because arbitrageurs do not share all their knowledge with investors,and cultivate secrecy to protect their knowledge from imitation.Even if the investors were told more about what arbitrageurs were doing,they would have a difficult time deciding whether what they heard was true.Implicitly,we are assuming that the underlying structural model is sufficiently nonstationary and high dimen- sional that investors are unable to infer the underlying structure of the model from past returns data.As a result,they only use simple updating rules based on past performance.In particular,investors are assumed to form posterior beliefs about future returns of the arbitrageur based only on their prior and any observations of his arbitrage returns. Under these informational assumptions,individual arbitrageurs who expe- rience relatively poor returns in a given period lose market share to those with better returns.Moreover,since all arbitrageurs in a given segment are taking the same positions,they all attract or lose investors simultaneously,depending on the performance of their common arbitrage strategy.Specifically,investors aggregate supply of funds to the arbitrageurs in a particular segment at time 2 is an increasing function of arbitrageurs'gross return between time 1 and time 2(call this performance-based-arbitrage or PBA).Denoting this function by G,and recognizing that the return on the asset is given by p2lp1,the arbitrageurs'supply of funds at t =2 is given by: F2=F1*G{(D/F1)*(p2/p)+(F1-D)/F}, with G(1)=1,G'≥1,andG"≤0. (4) If arbitrageurs do as well as some benchmark given by performance of arbi- trageurs in other markets,which for simplicity we assume to be zero return, they neither gain nor lose funds under management.However,they gain(lose) funds if they outperform(under perform)that benchmark.Because of the See Lakonishok,Shleifer,and Vishny(1992)for a description of the agency problems in the money management industry

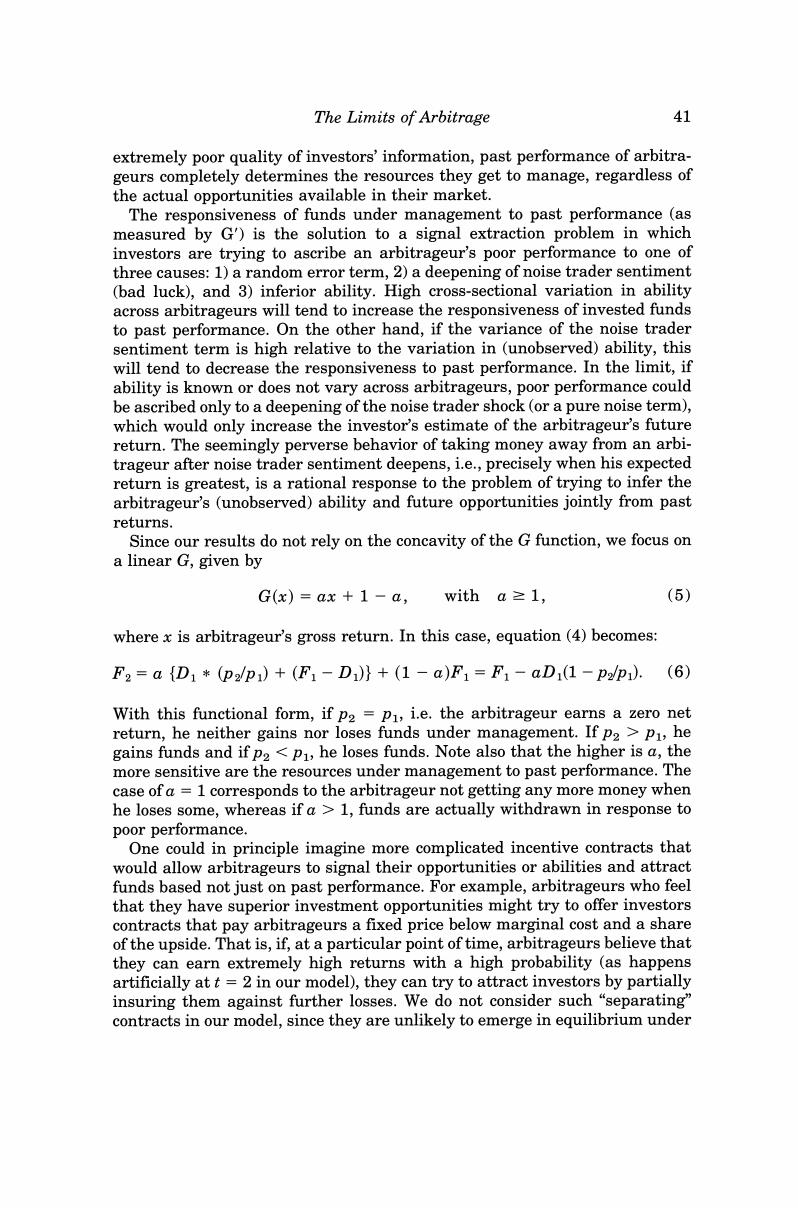

The Limits of Arbitrage 41 extremely poor quality of investors'information,past performance of arbitra- geurs completely determines the resources they get to manage,regardless of the actual opportunities available in their market. The responsiveness of funds under management to past performance (as measured by G')is the solution to a signal extraction problem in which investors are trying to ascribe an arbitrageur's poor performance to one of three causes:1)a random error term,2)a deepening of noise trader sentiment (bad luck),and 3)inferior ability.High cross-sectional variation in ability across arbitrageurs will tend to increase the responsiveness of invested funds to past performance.On the other hand,if the variance of the noise trader sentiment term is high relative to the variation in (unobserved)ability,this will tend to decrease the responsiveness to past performance.In the limit,if ability is known or does not vary across arbitrageurs,poor performance could be ascribed only to a deepening of the noise trader shock (or a pure noise term), which would only increase the investor's estimate of the arbitrageur's future return.The seemingly perverse behavior of taking money away from an arbi- trageur after noise trader sentiment deepens,i.e.,precisely when his expected return is greatest,is a rational response to the problem of trying to infer the arbitrageur's (unobserved)ability and future opportunities jointly from past returns. Since our results do not rely on the concavity of the G function,we focus on a linear G,given by G(x)=ax+1-a,with a≥1, (5) where x is arbitrageur's gross return.In this case,equation(4)becomes: F2=a{D1*(p2/p)+(F1-D)}+(1-a)F1=F1-aD(1-p2/p.(6) With this functional form,if p2=p1,i.e.the arbitrageur earns a zero net return,he neither gains nor loses funds under management.If p2>p1,he gains funds and if p2<p,he loses funds.Note also that the higher is a,the more sensitive are the resources under management to past performance.The case of a 1 corresponds to the arbitrageur not getting any more money when he loses some,whereas if a 1,funds are actually withdrawn in response to poor performance. One could in principle imagine more complicated incentive contracts that would allow arbitrageurs to signal their opportunities or abilities and attract funds based not just on past performance.For example,arbitrageurs who feel that they have superior investment opportunities might try to offer investors contracts that pay arbitrageurs a fixed price below marginal cost and a share of the upside.That is,if,at a particular point of time,arbitrageurs believe that they can earn extremely high returns with a high probability (as happens artificially at t=2 in our model),they can try to attract investors by partially insuring them against further losses.We do not consider such "separating" contracts in our model,since they are unlikely to emerge in equilibrium under