Energies 2015,8 11006 interventions;(2)discrete interventions.These approaches mainly provide occupants with the information about their consumption behaviors and associated impacts.The continuous intervention typically includes occupancy interactions(peer pressure and word-of-mouth)and continuous feedback techniques [110-112]. The discrete intervention mainly includes green community-based social marketing campaigns,energy efficiency education and training,and discrete feedback techniques [104,113-115].Social marketing campaigns are some commercial marketing techniques for the purpose of social engagement to influence occupants to change their social behaviors in order to save energy in built environments [116,117]. Education and training are also important for improving occupants'knowledge regarding energy-saving behaviors.Verplanken and Wood [104]and Gockeritz et al.[105]discussed how improving occupants'energy behaviors first requires changing individuals'beliefs and intentions regarding energy use.In this context,periodically holding energy meetings and workshops for occupants in individual commercial buildings has shown to be effective in improving energy-saving knowledge of built environments.In particular,these discrete interventions educate occupants about how to conserve energy, and occupants can share their energy-saving knowledge with each other through continuous interventions. Some consider combining discrete and continuous interventions as the most ideal and effective intervention technique. In addition to dividing interventions into continuous and discrete categories (see Figure 3), Archer et al.[118]divided the models motivating energy-saving behaviors into two groups: (1)rational-economic model;and (2)attitude model.In the rational-economic model,occupants are assumed to perform energy-saving behaviors that are economically advantageous.In the attitude model, occupant energy-saving behaviors result from promising and desirable attitudes about conservation. While occupancy-focused interventions assume the non-energy-saving behavior of occupants and work to improve occupants'behaviors,the rational-economic model assumes occupants have energy-saving behaviors.However,the attitude model needs occupancy-focused intervention to change the occupants' attitude to saving energy Occupancy Interactions Continuous Interventions Continuous Feedback Techniques Occupancy-focused Discrete Feedback Interventions Techniques Green Social Marketing Discrete Interventions Campaigns Energy Efficiency Education and Training Figure 3.Occupancy-focused interventions for improving energy-use behaviors [12,79]. It is noteworthy that the influence of an intervention technique significantly depends on social structures/networks within the built environment [85,119].In fact,organizational network and structure dynamics determine occupant engagement levels with an intervention technique,and therefore structures/networks could impact the results achieved by employing an intervention tool for improving energy-saving behaviors [68].Misunderstanding the influence of social structures might change occupants'behaviors into bad habits,a concept known as the rebound effect [120].Some intervention

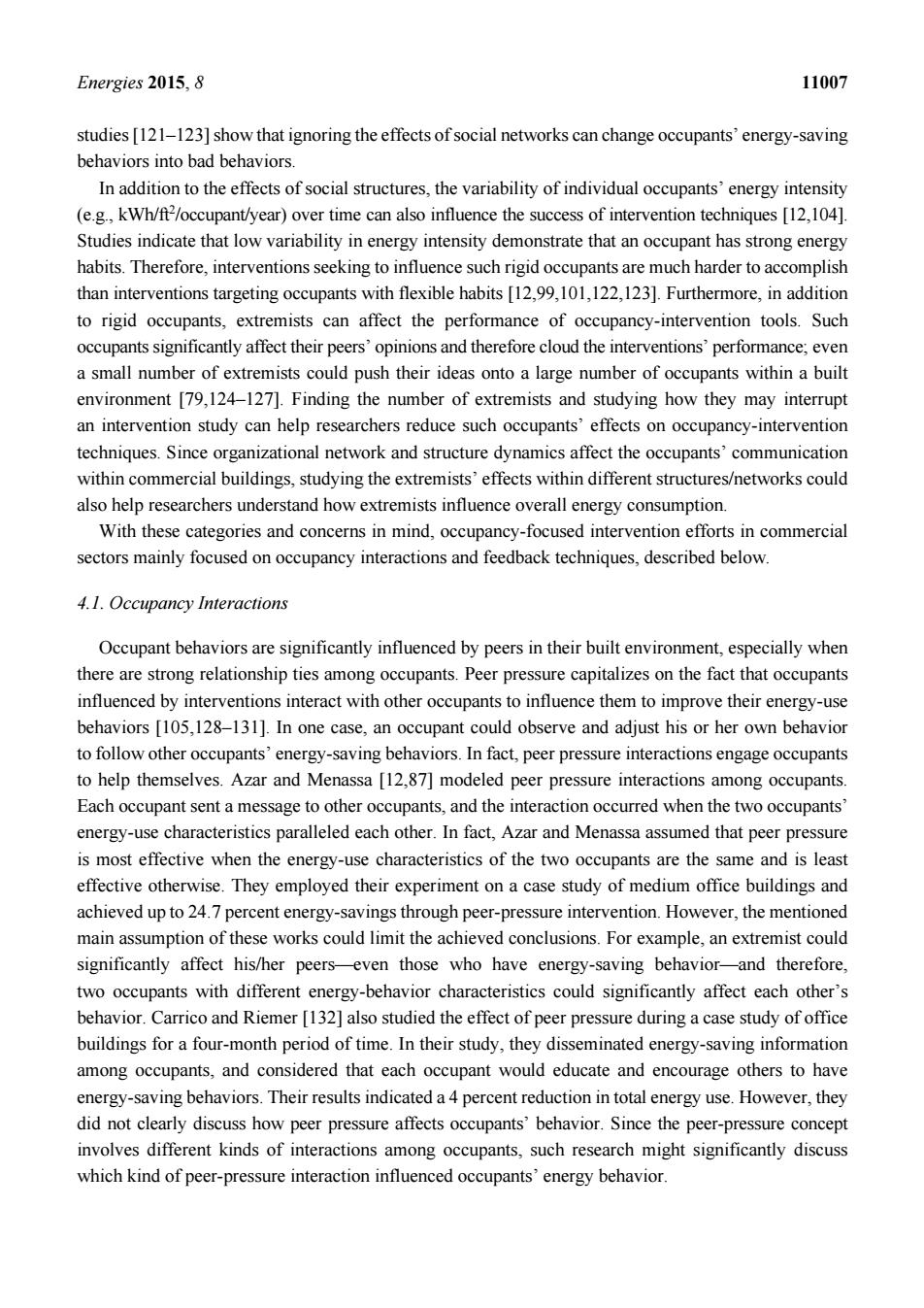

Energies 2015, 8 11006 interventions; (2) discrete interventions. These approaches mainly provide occupants with the information about their consumption behaviors and associated impacts. The continuous intervention typically includes occupancy interactions (peer pressure and word-of-mouth) and continuous feedback techniques [110–112]. The discrete intervention mainly includes green community-based social marketing campaigns, energy efficiency education and training, and discrete feedback techniques [104,113–115]. Social marketing campaigns are some commercial marketing techniques for the purpose of social engagement to influence occupants to change their social behaviors in order to save energy in built environments [116,117]. Education and training are also important for improving occupants’ knowledge regarding energy-saving behaviors. Verplanken and Wood [104] and Göckeritz et al. [105] discussed how improving occupants’ energy behaviors first requires changing individuals’ beliefs and intentions regarding energy use. In this context, periodically holding energy meetings and workshops for occupants in individual commercial buildings has shown to be effective in improving energy-saving knowledge of built environments. In particular, these discrete interventions educate occupants about how to conserve energy, and occupants can share their energy-saving knowledge with each other through continuous interventions. Some consider combining discrete and continuous interventions as the most ideal and effective intervention technique. In addition to dividing interventions into continuous and discrete categories (see Figure 3), Archer et al. [118] divided the models motivating energy-saving behaviors into two groups: (1) rational-economic model; and (2) attitude model. In the rational-economic model, occupants are assumed to perform energy-saving behaviors that are economically advantageous. In the attitude model, occupant energy-saving behaviors result from promising and desirable attitudes about conservation. While occupancy-focused interventions assume the non-energy-saving behavior of occupants and work to improve occupants’ behaviors, the rational-economic model assumes occupants have energy-saving behaviors. However, the attitude model needs occupancy-focused intervention to change the occupants’ attitude to saving energy. Figure 3. Occupancy-focused interventions for improving energy-use behaviors [12,79]. It is noteworthy that the influence of an intervention technique significantly depends on social structures/networks within the built environment [85,119]. In fact, organizational network and structure dynamics determine occupant engagement levels with an intervention technique, and therefore structures/networks could impact the results achieved by employing an intervention tool for improving energy-saving behaviors [68]. Misunderstanding the influence of social structures might change occupants’ behaviors into bad habits, a concept known as the rebound effect [120]. Some intervention Occupancy-focused Interventions Continuous Interventions Occupancy Interactions Continuous Feedback Techniques Discrete Interventions Discrete Feedback Techniques Green Social Marketing Campaigns Energy Efficiency Education and Training

Energies 2015,8 11007 studies [121-123]show that ignoring the effects of social networks can change occupants'energy-saving behaviors into bad behaviors. In addition to the effects of social structures,the variability of individual occupants'energy intensity (e.g.,kWh/ft2/occupant/year)over time can also influence the success of intervention techniques [12,104]. Studies indicate that low variability in energy intensity demonstrate that an occupant has strong energy habits.Therefore,interventions seeking to influence such rigid occupants are much harder to accomplish than interventions targeting occupants with flexible habits [12,99,101,122,123].Furthermore,in addition to rigid occupants,extremists can affect the performance of occupancy-intervention tools.Such occupants significantly affect their peers'opinions and therefore cloud the interventions'performance;even a small number of extremists could push their ideas onto a large number of occupants within a built environment [79,124-127].Finding the number of extremists and studying how they may interrupt an intervention study can help researchers reduce such occupants'effects on occupancy-intervention techniques.Since organizational network and structure dynamics affect the occupants'communication within commercial buildings,studying the extremists'effects within different structures/networks could also help researchers understand how extremists influence overall energy consumption. With these categories and concerns in mind,occupancy-focused intervention efforts in commercial sectors mainly focused on occupancy interactions and feedback techniques,described below. 4.1.Occupancy Interactions Occupant behaviors are significantly influenced by peers in their built environment,especially when there are strong relationship ties among occupants.Peer pressure capitalizes on the fact that occupants influenced by interventions interact with other occupants to influence them to improve their energy-use behaviors [105,128-131].In one case,an occupant could observe and adjust his or her own behavior to follow other occupants'energy-saving behaviors.In fact,peer pressure interactions engage occupants to help themselves.Azar and Menassa [12,87]modeled peer pressure interactions among occupants. Each occupant sent a message to other occupants,and the interaction occurred when the two occupants' energy-use characteristics paralleled each other.In fact,Azar and Menassa assumed that peer pressure is most effective when the energy-use characteristics of the two occupants are the same and is least effective otherwise.They employed their experiment on a case study of medium office buildings and achieved up to 24.7 percent energy-savings through peer-pressure intervention.However,the mentioned main assumption of these works could limit the achieved conclusions.For example,an extremist could significantly affect his/her peers-even those who have energy-saving behavior-and therefore, two occupants with different energy-behavior characteristics could significantly affect each other's behavior.Carrico and Riemer [132]also studied the effect of peer pressure during a case study of office buildings for a four-month period of time.In their study,they disseminated energy-saving information among occupants,and considered that each occupant would educate and encourage others to have energy-saving behaviors.Their results indicated a 4 percent reduction in total energy use.However,they did not clearly discuss how peer pressure affects occupants'behavior.Since the peer-pressure concept involves different kinds of interactions among occupants,such research might significantly discuss which kind of peer-pressure interaction influenced occupants'energy behavior

Energies 2015, 8 11007 studies [121–123] show that ignoring the effects of social networks can change occupants’ energy-saving behaviors into bad behaviors. In addition to the effects of social structures, the variability of individual occupants’ energy intensity (e.g., kWh/ft2 /occupant/year) over time can also influence the success of intervention techniques [12,104]. Studies indicate that low variability in energy intensity demonstrate that an occupant has strong energy habits. Therefore, interventions seeking to influence such rigid occupants are much harder to accomplish than interventions targeting occupants with flexible habits [12,99,101,122,123]. Furthermore, in addition to rigid occupants, extremists can affect the performance of occupancy-intervention tools. Such occupants significantly affect their peers’ opinions and therefore cloud the interventions’ performance; even a small number of extremists could push their ideas onto a large number of occupants within a built environment [79,124–127]. Finding the number of extremists and studying how they may interrupt an intervention study can help researchers reduce such occupants’ effects on occupancy-intervention techniques. Since organizational network and structure dynamics affect the occupants’ communication within commercial buildings, studying the extremists’ effects within different structures/networks could also help researchers understand how extremists influence overall energy consumption. With these categories and concerns in mind, occupancy-focused intervention efforts in commercial sectors mainly focused on occupancy interactions and feedback techniques, described below. 4.1. Occupancy Interactions Occupant behaviors are significantly influenced by peers in their built environment, especially when there are strong relationship ties among occupants. Peer pressure capitalizes on the fact that occupants influenced by interventions interact with other occupants to influence them to improve their energy-use behaviors [105,128–131]. In one case, an occupant could observe and adjust his or her own behavior to follow other occupants’ energy-saving behaviors. In fact, peer pressure interactions engage occupants to help themselves. Azar and Menassa [12,87] modeled peer pressure interactions among occupants. Each occupant sent a message to other occupants, and the interaction occurred when the two occupants’ energy-use characteristics paralleled each other. In fact, Azar and Menassa assumed that peer pressure is most effective when the energy-use characteristics of the two occupants are the same and is least effective otherwise. They employed their experiment on a case study of medium office buildings and achieved up to 24.7 percent energy-savings through peer-pressure intervention. However, the mentioned main assumption of these works could limit the achieved conclusions. For example, an extremist could significantly affect his/her peers—even those who have energy-saving behavior—and therefore, two occupants with different energy-behavior characteristics could significantly affect each other’s behavior. Carrico and Riemer [132] also studied the effect of peer pressure during a case study of office buildings for a four-month period of time. In their study, they disseminated energy-saving information among occupants, and considered that each occupant would educate and encourage others to have energy-saving behaviors. Their results indicated a 4 percent reduction in total energy use. However, they did not clearly discuss how peer pressure affects occupants’ behavior. Since the peer-pressure concept involves different kinds of interactions among occupants, such research might significantly discuss which kind of peer-pressure interaction influenced occupants’ energy behavior