MODIGLIANI AND MILLER:THEORY OF INVESTMENT 271 Since we have already shown that arbitrage will also prevent Va from being larger than Vi,we can conclude that in equilibrium we must have V2=Vi,as stated in Proposition I. Proposition II.From Proposition I we can derive the following propo- sition concerning the rate of return on common stock in companies whose capital structure includes some debt:the expected rate of return or yield,i,on the stock of any company j belonging to the kth class is a linear function of leverage as follows: (8) i=p张十(p%-)D/S That is,the expected yield of a share of stock is equal to the appropriate capitalization rate pr for a pure equity stream in the class,plus a premium related to financial risk equal to the debt-to-equity ratio times the spread betweeen ps and r.Or equivalently,the market price of any share of stock is given by capitalizing its expected return at the continuously variable rate i;of (8).12 A number of writers have stated close equivalents of our Proposition I although by appealing to intuition rather than by attempting a proof and only to insist immediately that the results were not applicable to the actual capital markets.s Proposition II,however,so far as we have been able to discover is new.To establish it we first note that,by definition, the expected rate of return,i,is given by: Xj-rDj (9) )三 Si From Proposition I,equation (3),we know that: Xj=pL(S;+Di). Substituting in(9)and simplifying,we obtain equation(8). To illustrate,suppose=1000,D=4000,=5per cent and=10per cent.These values imply that V=10,000 and S=6000 by virtue of Proposition I.The expected yield or rate of return per share is then: i-100-20-1+1-.040=135 per cet.. 6000 6000 1 See,for example,J.B.Williams [21,esp.pp.72-73];David Durand [3];and W.A. Morton [15].None of these writers describe in any detail the mechanism which is supposed to keep the average cost of capital constant under changes in capital structure.They seem,how- ever,to be visualizing the equilibrating mechanism in terms of switches by investors between stocks and bonds as the yields of each get out of line with their"riskiness."This is an argu- ment quite different from the pure arbitrage mechanism underlying our proof,and the differ- ence is crucial.Regarding Proposition I as resting on investors'attitudes toward risk leads inevitably to a misunderstanding of many factors influencing relative yields such as,for ex- ample,limitations on the portfolio composition of financial institutions.See below,esp. Section I.D. 1Morton does make reference to a linear yield function but only"...for the sake of sim- plicity and because the particular function used makes no essential difference in my conclu- sions"[15,p.443,note 21. This content downloaded from 202.120.21.61 on Thu,30 Nov 201707:07:36 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

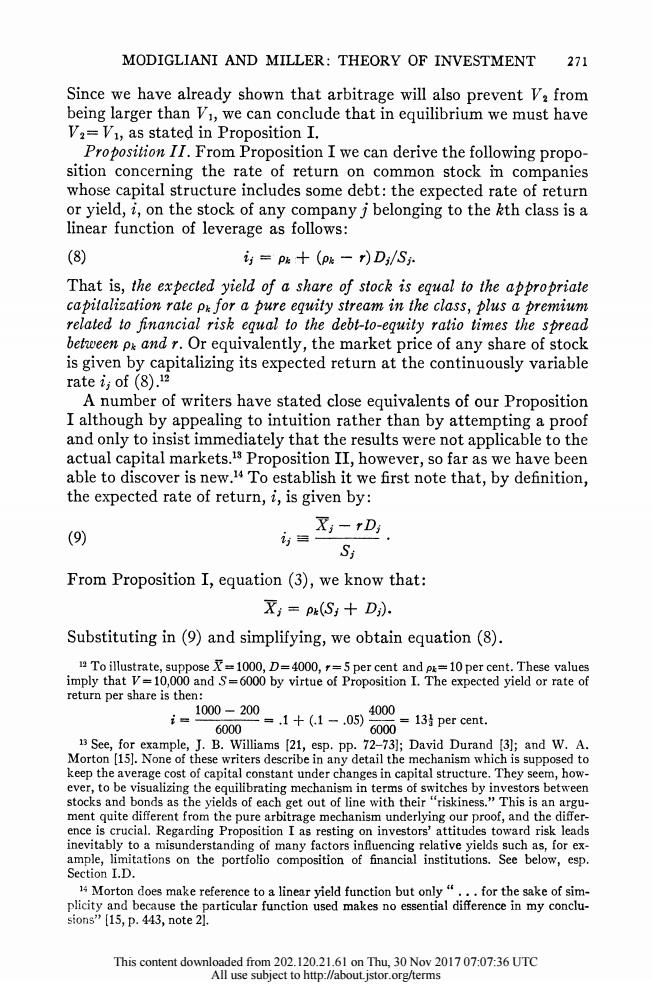

MODIGLIANI AND MILLER: THEORY OF INVESTMENT 271 Since we have already shown that arbitrage will also prevent V2 from being larger than VI, we can conclude that in equilibrium we must have V2= VI, as stated in Proposition I. Proposition II. From Proposition I we can derive the following propo- sition concerning the rate of return on common stock in companies whose capital structure includes some debt: the expected rate of return or yield, i, on the stock of any company j belonging to the kth class is a linear function of leverage as follows: (8) = pk + (Pk - r) DJ/Sj. That is, the expected yield of a share of stock is equal to the appropriate capitalization rate pk for a pure equity stream in the class, plus a premium related to financial risk equal to the debt-to-equity ratio times the spread between pk and r. Or equivalently, the market price of any share of stock is given by capitalizing its expected return at the continuously variable rate ij of (8).12 A number of writers have stated close equivalents of our Proposition I although by appealing to intuition rather than by attempting a proof and only to insist immediately that the results were not applicable to the actual capital markets.'3 Proposition II, however, so far as we have been able to discover is new.14 To establish it we first note that, by definition, the expected rate of return, i, is given by: Xi2- rD. (9)ij - Si From Proposition I, equation (3), we know that: Xi = pk(Sj + Dj). Substituting in (9) and simplifying, we obtain equation (8). 12 To illustrate, suppose X= 1000, D=4000, r= 5 per cent and pk= 10 per cent. These values imply that V= 10,000 and S= 6000 by virtue of Proposition I. The expected yield or rate of return per share is then: 1000 - 200 4000 6000 6000 3 's See, for example, J. B. Williams [21, esp. pp. 72-73]; David Durand [3]; and W. A. Morton [15]. None of these writers describe in any detail the mechanism which is supposed to keep the average cost of capital constant under changes in capital structure. They seem, how- ever, to be visualizing the equilibrating mechanism in terms of switches by investors between stocks and bonds as the yields of each get out of line with their "riskiness." This is an argu- ment quite different from the pure arbitrage mechanism underlying our proof, and the differ- ence is crucial. Regarding Proposition I as resting on investors' attitudes toward risk leads inevitably to a misunderstanding of many factors influencing relative yields such as, for ex- ample, limitations on the portfolio composition of financial institutions. See below, esp. Section I.D. 14 Morton does make reference to a linear yield function but only" .. for the sake of sim- plicity and because the particular function used makes no essential difference in my conclu- sions" [15, p. 443, note 21. This content downloaded from 202.120.21.61 on Thu, 30 Nov 2017 07:07:36 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

272 THE AMERICAN ECONOMIC REVIEW C.Some Qualifications and Extensions of the Basic Propositions The methods and results developed so far can be extended in a num- ber of useful directions,of which we shall consider here only three:(1) allowing for a corporate profits tax under which interest payments are deductible;(2)recognizing the existence of a multiplicity of bonds and interest rates;and(3)acknowledging the presence of market imperfec- tions which might interfere with the process of arbitrage.The first two will be examined briefly in this section with some further attention given to the tax problem in Section II.Market imperfections will be dis- cussed in Part D of this section in the course of a comparison of our re- sults with those of received doctrines in the field of finance. Effects of the Present Method of Taxing Corporations.The deduction of interest in computing taxable corporate profits will prevent the arbi- trage process from making the value of all firms in a given class propor- tional to the expected returns generated by their physical assets.In- stead,it can be shown(by the same type of proof used for the original version of Proposition I)that the market values of firms in each class must be proportional in equilibrium to their expected return net of taxes(that is,to the sum of the interest paid and expected net stock- holder income).This means we must replace each X;in the original ver- sions of Propositions I and II with a new variable X,representing the total income net of taxes generated by the firm: (10) X=(X;-rD)(1-)十rD;=元,r十rD, where represents the expected net income accruing to the common stockholders and r stands for the average rate of corporate income tax.5 After making these substitutions,the propositions,when adjusted for taxes,continue to have the same form as their originals.That is,Propo- sition I becomes: X (11) p,for any firm in class k, Vi and Proposition II becomes (12) 元” =p+(p'-)D/S Si where p&is the capitalization rate for income net of taxes in class k. Although the form of the propositions is unaffected,certain interpre- tations must be changed.In particular,the after-tax capitalization rate 15 For simplicity,we shall ignore throughout the tiny element of progression in our present corporate tax and treat r as a constant independent of (Xi-rD). This content downloaded from 202.120.21.61 on Thu,30 Nov 201707:07:36 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

272 THE AMERICAN ECONOMIC REVIEW C. Some Qualifications and Extensions of the Basic Propositions The methods and results developed so far can be extended in a num- ber of useful directions, of which we shall consider here only three: (1) allowing for a corporate profits tax under which interest payments are deductible; (2) recognizing the existence of a multiplicity of bonds and interest rates; and (3) acknowledging the presence of market imperfec- tions which might interfere with the process of arbitrage. The first two will be examined briefly in this section with some further attention given to the tax problem in Section II. Market imperfections will be dis- cussed in Part D of this section in the course of a comparison of our re- sults with those of received doctrines in the field of finance. Effects of the Present Method of Taxing Corporations. The deduction of interest in computing taxable corporate profits will prevent the arbi- trage process from making the value of all firms in a given class propor- tional to the expected returns generated by their physical assets. In- stead, it can be shown (by the same type of proof used for the original version of Proposition I) that the market values of firms in each class must be proportional in equilibrium to their expected return net of taxes (that is, to the sum of the interest paid and expected net stock- holder income). This means we must replace each Xi in the original ver- sions of Propositions I and II with a new variable Xj7 representing the total income net of taxes generated by the firm: (10) XJr--(Xi - rDi)(1 - T) + rDi 7jT + rDj, where fr-t represents the expected net income accruing to the common stockholders and r stands for the average rate of corporate income tax.'5 After making these substitutions, the propositions, when adjusted for taxes, continue to have the same form as their originals. That is, Propo- sition I becomes: 27 (11) _= Pk, for any firm in class k, and Proposition II becomes (12) rP + (Pkr - r) Dl,/S Si where Pkl is the capitalization rate for income net of taxes in class k. Although the form of the propositions is unaffected, certain interpre- tations must be changed. In particular, the after-tax capitalization rate 15 For simplicity, we shall ignore throughout the tiny element of progression in our present corporate tax and treat r as a constant independent of (Xi-rD,). This content downloaded from 202.120.21.61 on Thu, 30 Nov 2017 07:07:36 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

MODIGLIANI AND MILLER:THEORY OF INVESTMENT 273 P can no longer be identified with the "average cost of capital"which is p=Xi/Vi.The difference between p and the "true"average cost of capital,as we shall see,is a matter of some relevance in connection with investment planning within the firm(Section II).For the description of market bchavior,however,which is our immediate concern here,the dis- tinction is not essential.To simplify presentation,therefore,and to pre- serve continuity with the terminology in the standard literature we shall continue in this section to refer to pa as the average cost of capital, though strictly speaking this identification is correct only in the absence of taxes. Effects of a Plurality of Bonds and Interest Rates.In existing capital markets we find not one,but a whole family of interest rates varying with maturity,with the technical provisions of the loan and,what is most relevant for present purposes,with the financial condition of the borrower.16 Economic theory and market experience both suggest that the yields demanded by lenders tend to increase with the debt-equity ratio of the borrowing firm (or individual).If so,and if we can assume as a first approximation that this yield curve,r=r(D/S),whatever its precise form,is the same for all borrowers,then we can readily extend our propositions to the case of a rising supply curve for borrowed funds.17 Proposition I is actually unaffected in form and interpretation by the fact that the rate of interest may rise with leverage;while the average cost of borrowed funds will tend to increase as debt rises,the average cost of funds from all sources will still be independent of leverage (apart from the tax effect).This conclusion follows directly from the ability of those who engage in arbitrage to undo the leverage in any financial structure by acquiring an appropriately mixed portfolio of bonds and stocks.Because of this ability,the ratio of earnings (before interest charges)to market value--i.e.,the average cost of capital from all 16 We shall not consider here the extension of the analysis to encompass the time structure of interest rates.Although some of the problems posed by the time structure can be handled with- in our comparative statics framework,an adequate discussion would require a separate paper. 17 We can also develop a theory of bond valuation along lines essentially parallel to those fol- lowed for the case of shares.We conjecture that the curve of bond yields as a function of lever- age will turn out to be a nonlinear one in contrast to the linear function of leverage developed for common shares.However,we would also expect that the rate of increase in the yield on new issues would not be substantial in practice.This relatively slow rise would reflect the fact that interest rate increases by themselves can never be completely satisfactory to creditors as compensation for their increased risk.Such increases may simply serve to raise r so high rela- tive to p that they become self-defeating by giving rise to a situation in which even normal fluctuations in earnings may force the company into bankruptcy.The difficulty of borrowing more,therefore,tends to show up in the usual case not so much in higher rates as in the form of increasingly stringent restrictions imposed on the company's management and finances by the creditors;and ultimately in a complete inability to obtain new borrowed funds,at least from the institutional investors who normally set:the standards in the market for bonds. This content downloaded from 202.120.21.61 on Thu,30 Nov 201707:07:36 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

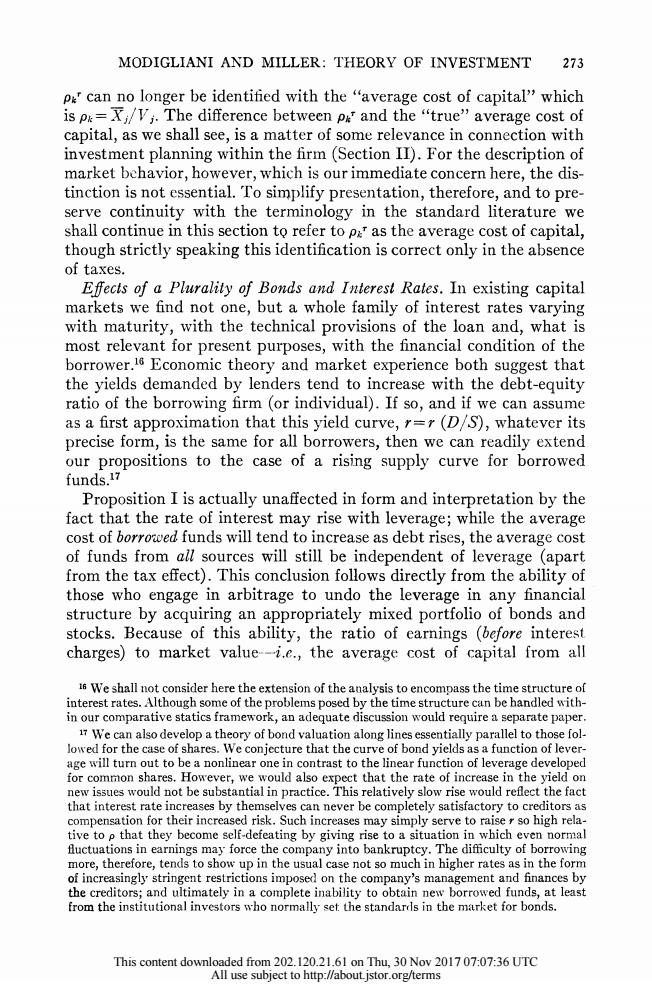

MODIGLIANI AND MILLER: THEORY OF INVESTMENT 273 PkT can no longer be identified with the "average cost of capital" which iS Pk = XjVTIj. The difference between Pk and the "true" average cost of capital, as we shall see, is a matter of some relevance in connection with investment planning within the firm (Section II). For the description of market behavior, however, which is our immediate concern here, the dis- tinction is not essential. To simplify presentation, therefore, and to pre- serve continuity with the terminology in the standard literature we shall continue in this section tQ refer to Pk as the average cost of capital, though strictly speaking this identification is correct only in the absence of taxes. Effects of a Plurality of Bonds and Interest Rates. In existing capital markets we find not one, but a whole family of interest rates varying with maturity, with the technical provisions of the loan and, what is most relevant for present purposes, with the financial condition of the borrower.16 Economic theory and market experience both suggest that the yields demanded by lenders tend to increase with the debt-equity ratio of the borrowing firm (or individual). If so, and if we can assume as a first approximation that this yield curve, r = r (D/S), whatever its precise form, is the same for all borrowers, then we can readily extend our propositions to the case of a rising supply curve for borrowed funds.'7 Proposition I is actually unaffected in form and interpretation by the fact that the rate of interest may rise with leverage; while the average cost of borrowed funds will tend to increase as debt rises, the average cost of funds from all sources will still be independent of leverage (apart from the tax effect). This conclusion follows directly from the ability of those who engage in arbitrage to undo the leverage in any financial structure by acquiring an appropriately mixed portfolio of bonds and stocks. Because of this ability, the ratio of earnings (before interest. charges) to market value--i.e., the average cost of capital from all 16 We shall not consider here the extension of the analysis to encompass the time structure of interest rates. Although some of the problems posed by the time structure can be handled with- in our comparative statics framework, an adequate discussion would require a separate paper. 17 We can also develop a theory of bond valuation along lines essentially parallel to those fol- lowved for the case of shares. We conjecture that the curve of bond yields as a function of lever- age will turn out to be a nonlinear one in contrast to the linear function of leverage developed for common shares. However, we would also expect that the rate of increase in the yield on new issues would not be substantial in practice. This relatively slow rise would reflect the fact that interest rate increases by themselves can never be completely satisfactory to creditors as compensation for their increased risk. Such increases may simply serve to raise r so high rela- tive to p that they become self-defeating by giving rise to a situation in which even norrmal fluctuations in earnings may force the company into bankruptcy. The difficulty of borrowing more, therefore, tends to show up in the usual case not so much in higher rates as in the form of increasingly stringent restrictions imposed on the company's management and finances by the creditors; and ultimately in a comnplete inability to obtain new borrowed funds, at least from the instituitional investors who normally set the standar(ds in the market for bonds. This content downloaded from 202.120.21.61 on Thu, 30 Nov 2017 07:07:36 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms