ased its nershin interest last vear in ea of its"Big Four” Express.Coca-CoBMd Wells Fargo.We purchascdtiohr of IBM (increasnu ownership to 84%versus .8%at yearend 2014)and Wells Fargo (going to98%from 94%).At the othe in Ars rais to 15.6%In case you think these seemingly small changes aren't important,consider this math:For the four companies in aggregate,each increase of one percentage point in our ownership raises Berkshire's portion of their annual eamings by about $500 million ssess excellent businesses and are run by managers who are both talented and qity range from exc lent to staggering.At 复steoeaaneopaaaeoEa3o If Berkshire' are used as the marker our on of the "Big Four's"2015 earning pay us-about $1.8 billion last year.But make no mistake:The ne earnings we don't report are every bit as valuable to us as the nortion Rerkshired own stock-a move that increases ture earnings wit us to lay out e retaine the h expect that the per-share eamnings of these four investees.in aggregate will grow substantially over time If gains do indeed materialize,dividends to Berkshire will increase and so,too,will our unrealized capital gains Our flexibility in capital allocation our willingness to invest large sums passively in non-controllec e over companies that limit themse ves ht.In like manner-well not exactly like manner our appetite operating businesses or passive investments doubleso chances of finding sensible uses for Berkshire' seyond that,having a h ho or ma securities gives us a stockpil tapped w an elephant-s ered to us It's an election year,and candidates can't stop speaking about our country's problems(which,of course. of this negative drumbeat,many Americans now believe that their children will not That view is dead wrong:The babies being bom in America today are the luckiest crop in history. American GDP per capita is now about $56,000.As I mentioned last year that-in real terms-is a boma leap far beyond the wildest dreams of my parents Americans in 1930.Rather they work far more efficiently and thereby produce far more This all erful trend i certain to continue:America's economic magic remains alive and well Some commentators hemoan owth in real GDP-and.ves.we would all like to see a higher rate.But let's do some simple math using the much-lamented2%figure.That rate,we will see.delivers astounding gains. >

‹ Berkshire increased its ownership interest last year in each of its “Big Four” investments – American Express, Coca-Cola, IBM and Wells Fargo. We purchased additional shares of IBM (increasing our ownership to 8.4% versus 7.8% at yearend 2014) and Wells Fargo (going to 9.8% from 9.4%). At the other two companies, Coca-Cola and American Express, stock repurchases raised our percentage ownership. Our equity in Coca-Cola grew from 9.2% to 9.3%, and our interest in American Express increased from 14.8% to 15.6%. In case you think these seemingly small changes aren’t important, consider this math: For the four companies in aggregate, each increase of one percentage point in our ownership raises Berkshire’s portion of their annual earnings by about $500 million. These four investees possess excellent businesses and are run by managers who are both talented and shareholder-oriented. Their returns on tangible equity range from excellent to staggering. At Berkshire, we much prefer owning a non-controlling but substantial portion of a wonderful company to owning 100% of a so-so business. It’s better to have a partial interest in the Hope Diamond than to own all of a rhinestone. If Berkshire’s yearend holdings are used as the marker, our portion of the “Big Four’s” 2015 earnings amounted to $4.7 billion. In the earnings we report to you, however, we include only the dividends they pay us – about $1.8 billion last year. But make no mistake: The nearly $3 billion of these companies’ earnings we don’t report are every bit as valuable to us as the portion Berkshire records. The earnings our investees retain are often used for repurchases of their own stock – a move that increases Berkshire’s share of future earnings without requiring us to lay out a dime. The retained earnings of these companies also fund business opportunities that usually turn out to be advantageous. All that leads us to expect that the per-share earnings of these four investees, in aggregate, will grow substantially over time. If gains do indeed materialize, dividends to Berkshire will increase and so, too, will our unrealized capital gains. Our flexibility in capital allocation – our willingness to invest large sums passively in non-controlled businesses – gives us a significant edge over companies that limit themselves to acquisitions they will operate. Woody Allen once explained that the advantage of being bi-sexual is that it doubles your chance of finding a date on Saturday night. In like manner – well, not exactly like manner – our appetite for either operating businesses or passive investments doubles our chances of finding sensible uses for Berkshire’s endless gusher of cash. Beyond that, having a huge portfolio of marketable securities gives us a stockpile of funds that can be tapped when an elephant-sized acquisition is offered to us. ************ It’s an election year, and candidates can’t stop speaking about our country’s problems (which, of course, only they can solve). As a result of this negative drumbeat, many Americans now believe that their children will not live as well as they themselves do. That view is dead wrong: The babies being born in America today are the luckiest crop in history. American GDP per capita is now about $56,000. As I mentioned last year that – in real terms – is a staggering six times the amount in 1930, the year I was born, a leap far beyond the wildest dreams of my parents or their contemporaries. U.S. citizens are not intrinsically more intelligent today, nor do they work harder than did Americans in 1930. Rather, they work far more efficiently and thereby produce far more. This all-powerful trend is certain to continue: America’s economic magic remains alive and well. Some commentators bemoan our current 2% per year growth in real GDP – and, yes, we would all like to see a higher rate. But let’s do some simple math using the much-lamented 2% figure. That rate, we will see, delivers astounding gains. 7

(Compound n tun percentage that would result by simply multiplying 25x 1.2% pro ce a staggering y need not shed tears for tomorrow's children. niddle-clas 尚 regularly e 's,how it will be divided and services between those people in their productiverand retirees between the healthy and the inrm between the inheritors and the Horatio Algers,between investors and workers and,in particular,between those with are va nighly by the ma ce and the equ ly dece orking Americans who lack battlefield:money and votes will be the weapons.Lobbying will remain a growth industry. as the roods and services in the future than they have in the will also dramatically improve.Nothing rivals the market system in producing what pe so,in de id what ole want don t ye now they want.N y p 15 hen young,cou not er For 240 vears it's been a terrible mistake to bet against America.and now is no time to start.America's golden goose of commerce and innovation will continue to lay more and larger l be hored ad prap me regeeround.Americv far berer he merica's social securty Considering this favorable tailwind.Bershr (dbebusineses)will ams e mana rs who succeed lie and me w share intrinsi (2)further their ca (4)repurchasing Berkshire shares when they are available at a meaningful discount from intrinsic value;and (5)ma

America’s population is growing about .8% per year (.5% from births minus deaths and .3% from net migration). Thus 2% of overall growth produces about 1.2% of per capita growth. That may not sound impressive. But in a single generation of, say, 25 years, that rate of growth leads to a gain of 34.4% in real GDP per capita. (Compounding’s effects produce the excess over the percentage that would result by simply multiplying 25 x 1.2%.) In turn, that 34.4% gain will produce a staggering $19,000 increase in real GDP per capita for the next generation. Were that to be distributed equally, the gain would be $76,000 annually for a family of four. Today’s politicians need not shed tears for tomorrow’s children. Indeed, most of today’s children are doing well. All families in my upper middle-class neighborhood regularly enjoy a living standard better than that achieved by John D. Rockefeller Sr. at the time of my birth. His unparalleled fortune couldn’t buy what we now take for granted, whether the field is – to name just a few – transportation, entertainment, communication or medical services. Rockefeller certainly had power and fame; he could not, however, live as well as my neighbors now do. Though the pie to be shared by the next generation will be far larger than today’s, how it will be divided will remain fiercely contentious. Just as is now the case, there will be struggles for the increased output of goods and services between those people in their productive years and retirees, between the healthy and the infirm, between the inheritors and the Horatio Algers, between investors and workers and, in particular, between those with talents that are valued highly by the marketplace and the equally decent hard-working Americans who lack the skills the market prizes. Clashes of that sort have forever been with us – and will forever continue. Congress will be the battlefield; money and votes will be the weapons. Lobbying will remain a growth industry. The good news, however, is that even members of the “losing” sides will almost certainly enjoy – as they should – far more goods and services in the future than they have in the past. The quality of their increased bounty will also dramatically improve. Nothing rivals the market system in producing what people want – nor, even more so, in delivering what people don’t yet know they want. My parents, when young, could not envision a television set, nor did I, in my 50s, think I needed a personal computer. Both products, once people saw what they could do, quickly revolutionized their lives. I now spend ten hours a week playing bridge online. And, as I write this letter, “search” is invaluable to me. (I’m not ready for Tinder, however.) For 240 years it’s been a terrible mistake to bet against America, and now is no time to start. America’s golden goose of commerce and innovation will continue to lay more and larger eggs. America’s social security promises will be honored and perhaps made more generous. And, yes, America’s kids will live far better than their parents did. ************ Considering this favorable tailwind, Berkshire (and, to be sure, a great many other businesses) will almost certainly prosper. The managers who succeed Charlie and me will build Berkshire’s per-share intrinsic value by following our simple blueprint of: (1) constantly improving the basic earning power of our many subsidiaries; (2) further increasing their earnings through bolt-on acquisitions; (3) benefiting from the growth of our investees; (4) repurchasing Berkshire shares when they are available at a meaningful discount from intrinsic value; and (5) making an occasional large acquisition. Management will also try to maximize results for you by rarely, if ever, issuing Berkshire shares. 8

Intrinsic Business Value is for Rer 2010 annual r port we laid out the three elementsone of them qualitative that we believe are the kevs to an estimation of Berkshire's intrinsic value.That discussion is reproduced in full on pages 113-114. Here is an update of the two quantitative factors:In 2015 our per-share cash and investments increased 8.3%to $159,794 (with our Kraft Heinz shares stated at market value),and earnings from our many businesses- nce unde 0%toS12,304 per share.We exclude in th cond factor of value.In arriving at our earnings figure.we deduct all corporate overhead.interest.depreciation.amortization and minority interests.Income taxes,though,are not deducted.That is,the earnings are pre-tax. h above because we are for the first time including insurance underwriting nbusiness eamings.We did not do that when we initially introduced Berkshire's two quantitative pillasof ce results ere then h ove ages.If th wind didn over time and ignored any of its gains or losses in our annual calculation of the second factor of value. Today,our insurance results are likely to be more stable than was the case a decade or two ago because we have deemphasized cntributed S1,118 per share to the srad-and-butter lines of bus of business.Last year g inc me e S12,304 per share of earnin renced in the se t vears.You should re well be unprofitable,perhaps substantially so. Since 1970.our per-share investments have increased at a rate of 18 9%compounded annually.and ou earings (including the underwriting results in both the initial and terminal year)have grown at a23.7%clip.It isno to that o camnings Now,let's examine the four major sectors of our operations.Each has vastly diff rent balance sheet and gh the ant and a n present them intent is to provide you with the information we would wish to have if our positions were reversed,with you being the reporting manager and we the absentee shareholders.(Don't get excited:this is not a switch we are considering.) Insurance Let's look first at ins D9)1 ch of that indu .tha Nationa mnity is the largest property-casualty by net worth. s carried on our

Intrinsic Business Value As much as Charlie and I talk about intrinsic business value, we cannot tell you precisely what that number is for Berkshire shares (nor, in fact, for any other stock). It is possible, however, to make a sensible estimate. In our 2010 annual report we laid out the three elements – one of them qualitative – that we believe are the keys to an estimation of Berkshire’s intrinsic value. That discussion is reproduced in full on pages 113-114. Here is an update of the two quantitative factors: In 2015 our per-share cash and investments increased 8.3% to $159,794 (with our Kraft Heinz shares stated at market value), and earnings from our many businesses – including insurance underwriting income – increased 2.1% to $12,304 per share. We exclude in the second factor the dividends and interest from the investments we hold because including them would produce a double-counting of value. In arriving at our earnings figure, we deduct all corporate overhead, interest, depreciation, amortization and minority interests. Income taxes, though, are not deducted. That is, the earnings are pre-tax. I used the italics in the paragraph above because we are for the first time including insurance underwriting income in business earnings. We did not do that when we initially introduced Berkshire’s two quantitative pillars of valuation because our insurance results were then heavily influenced by catastrophe coverages. If the wind didn’t blow and the earth didn’t shake, we made large profits. But a mega-catastrophe would produce red ink. In order to be conservative then in stating our business earnings, we consistently assumed that underwriting would break even over time and ignored any of its gains or losses in our annual calculation of the second factor of value. Today, our insurance results are likely to be more stable than was the case a decade or two ago because we have deemphasized catastrophe coverages and greatly expanded our bread-and-butter lines of business. Last year, our underwriting income contributed $1,118 per share to the $12,304 per share of earnings referenced in the second paragraph of this section. Over the past decade, annual underwriting income has averaged $1,434 per share, and we anticipate being profitable in most years. You should recognize, however, that underwriting in any given year could well be unprofitable, perhaps substantially so. Since 1970, our per-share investments have increased at a rate of 18.9% compounded annually, and our earnings (including the underwriting results in both the initial and terminal year) have grown at a 23.7% clip. It is no coincidence that the price of Berkshire stock over the ensuing 45 years has increased at a rate very similar to that of our two measures of value. Charlie and I like to see gains in both sectors, but our main goal is to build operating earnings. ************ Now, let’s examine the four major sectors of our operations. Each has vastly different balance sheet and income characteristics from the others. So we’ll present them as four separate businesses, which is how Charlie and I view them (though there are important and enduring economic advantages to having them all under one roof). Our intent is to provide you with the information we would wish to have if our positions were reversed, with you being the reporting manager and we the absentee shareholders. (Don’t get excited; this is not a switch we are considering.) Insurance Let’s look first at insurance. The property-casualty (“P/C”) branch of that industry has been the engine that has propelled our expansion since 1967, when we acquired National Indemnity and its sister company, National Fire & Marine, for $8.6 million. Today, National Indemnity is the largest property-casualty company in the world, as measured by net worth. Moreover, its intrinsic value is far in excess of the value at which it is carried on our books. 9

characteristics:P/C insurers receive 网ehog可杰is clle y we call "float that will eventually go to othe Though individual policies and come al daheanmeontofaoatninsurerhol sequently,as our And how we have grown.as the following table shows: ess grows,so Year Float (in millions) 1000 163 2000 27.871 2010 65,83 2015 87,722 Further gains in float will be tough to achieve.On the plus side,GEICO and several of our specialized operations re alm st certain to grow at a goo lip.Natic Inde nity s reinsurance divi on,hov dforholdingL in effect,is what the industry pays to hold its float.Competitive dynamics almost guarantee that the insuranc industry,despite the float income all its comp anies enjoy,will continue its dismal record of aming subnorma 00 er Am or erest rate that to come,ther by exacerbating the profit problems of insurers.It'sa good bet that industry results over the next ten wall short of those recorded in the past decade,particularly for those companies that specialize in As noted e early in on that whil n he deriting reuAll insrergive that message lip serviceAt Berkshire t is religion,Testa So how does our float affect intrinsic value?When Berkshire's book value is calculated,the fill amount of 0rtnoatisdkduct d as a fiability,Just as a lia a revol float

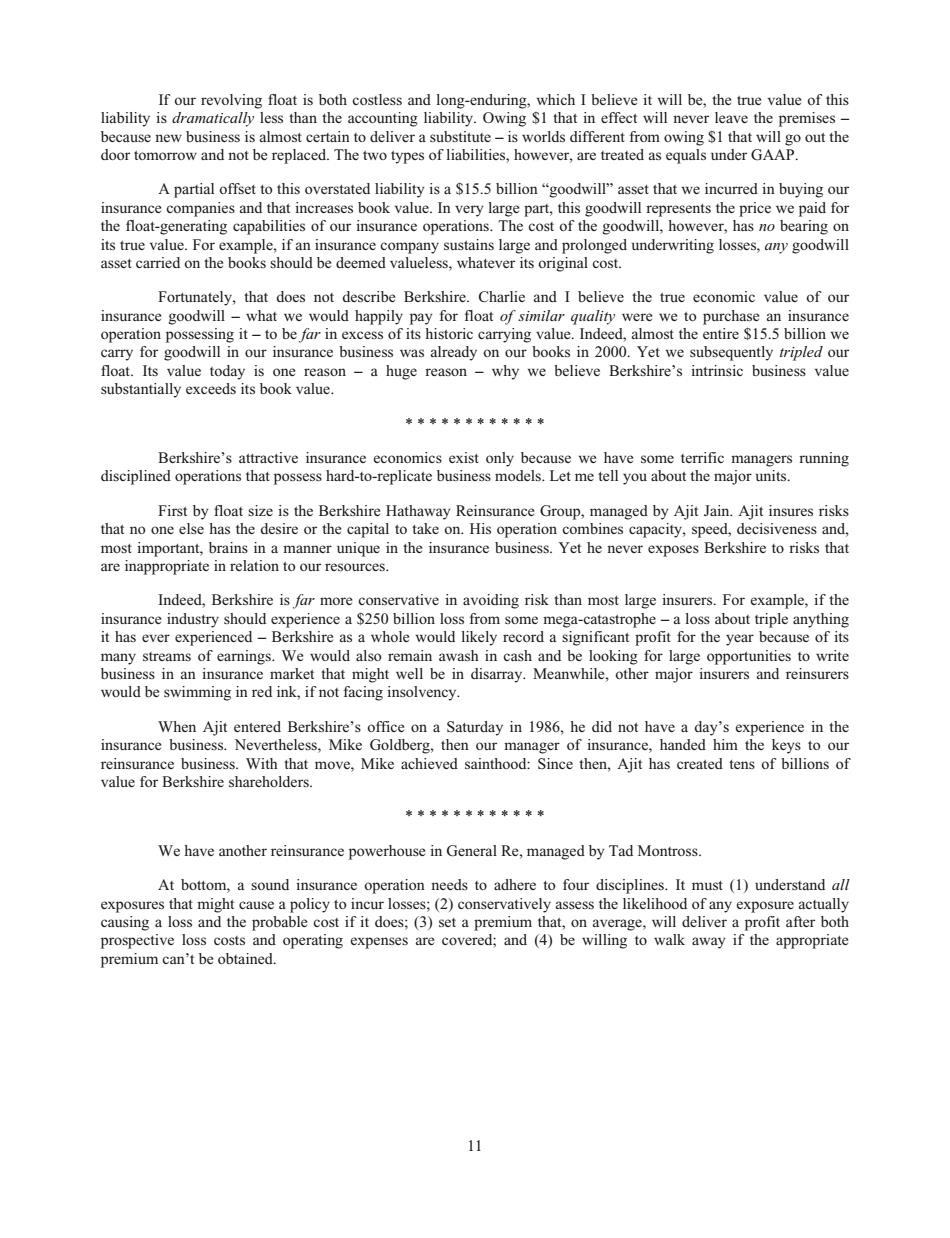

One reason we were attracted to the P/C business was its financial characteristics: P/C insurers receive premiums upfront and pay claims later. In extreme cases, such as those arising from certain workers’ compensation accidents, payments can stretch over many decades. This collect-now, pay-later model leaves P/C companies holding large sums – money we call “float” – that will eventually go to others. Meanwhile, insurers get to invest this float for their own benefit. Though individual policies and claims come and go, the amount of float an insurer holds usually remains fairly stable in relation to premium volume. Consequently, as our business grows, so does our float. And how we have grown, as the following table shows: Year Float (in millions) 1970 $ 39 1980 237 1990 1,632 2000 27,871 2010 65,832 2015 87,722 Further gains in float will be tough to achieve. On the plus side, GEICO and several of our specialized operations are almost certain to grow at a good clip. National Indemnity’s reinsurance division, however, is party to a number of run-off contracts whose float drifts downward. If we do in time experience a decline in float, it will be very gradual – at the outside no more than 3% in any year. The nature of our insurance contracts is such that we can never be subject to immediate or near-term demands for sums that are of significance to our cash resources. This structure is by design and is a key component in the strength of Berkshire’s economic fortress. It will never be compromised. If our premiums exceed the total of our expenses and eventual losses, we register an underwriting profit that adds to the investment income our float produces. When such a profit is earned, we enjoy the use of free money – and, better yet, get paid for holding it. Unfortunately, the wish of all insurers to achieve this happy result creates intense competition, so vigorous indeed that it sometimes causes the P/C industry as a whole to operate at a significant underwriting loss. This loss, in effect, is what the industry pays to hold its float. Competitive dynamics almost guarantee that the insurance industry, despite the float income all its companies enjoy, will continue its dismal record of earning subnormal returns on tangible net worth as compared to other American businesses. The prolonged period of low interest rates the world is now dealing with also virtually guarantees that earnings on float will steadily decrease for many years to come, thereby exacerbating the profit problems of insurers. It’s a good bet that industry results over the next ten years will fall short of those recorded in the past decade, particularly for those companies that specialize in reinsurance. As noted early in this report, Berkshire has now operated at an underwriting profit for 13 consecutive years, our pre-tax gain for the period having totaled $26.2 billion. That’s no accident: Disciplined risk evaluation is the daily focus of all of our insurance managers, who know that while float is valuable, its benefits can be drowned by poor underwriting results. All insurers give that message lip service. At Berkshire it is a religion, Old Testament style. So how does our float affect intrinsic value? When Berkshire’s book value is calculated, the full amount of our float is deducted as a liability, just as if we had to pay it out tomorrow and could not replenish it. But to think of float as strictly a liability is incorrect. It should instead be viewed as a revolving fund. Daily, we pay old claims and related expenses – a huge $24.5 billion to more than six million claimants in 2015 – and that reduces float. Just as surely, we each day write new business that will soon generate its own claims, adding to float. 10

If o volving float is hoth costless nduring which i believe it will be the value of thi liability is rmcless than the accounting liability.Owing$I that in effect will never leave the premises- A partial offset to this overstated liability is a15.5 billion"goodwill"asset that we incurred in buying our companies and th odwill.h its true value.For example,if an insurance com asset carried on the books should be deemed valueless,whatever its original cost. Fortunately,that does not describe Berkshire.Charlie and I believe the true economic value of our insurance goodwill what we would happily pay for float of simild we to purchase nng it -to be Jar in excess of its h float.Its value today is one reason-a huge reason-why we believe Berkshire's intrinsic business valu substantially exceeds its book value. 市幸市市率来率市市率中号 Berkshire srunning ital to take on His most important,brains in a manner unique in the insurance business.Yet he never exposes Berkshire to risks that are inappropriate in relation to our resources Indeed,Berkshire is far more conservative in avoiding risk than most large insurers.For example,if the from some mega-catastrophe ss about triple anything ain awash in cash and be looki rtunities to write business in an insurance market that might well be in disarray.Meanwhile,other major insurers and reinsurers would be swimming in red ink,if not facing insolvency. When Ajit entered Berkshire's office on a Saturday in 1986,he did not have a day's experience in the insurance business.Neverthe ess,Mike erg,then We have another reinsurance powerhouse in General Re,managed by Tad Montross. At bottom,a sound insurance operation needs to adhere to four disciplines.It must (1)understand all e and oper ting re appropr premium can't be obtained

If our revolving float is both costless and long-enduring, which I believe it will be, the true value of this liability is dramatically less than the accounting liability. Owing $1 that in effect will never leave the premises – because new business is almost certain to deliver a substitute – is worlds different from owing $1 that will go out the door tomorrow and not be replaced. The two types of liabilities, however, are treated as equals under GAAP. A partial offset to this overstated liability is a $15.5 billion “goodwill” asset that we incurred in buying our insurance companies and that increases book value. In very large part, this goodwill represents the price we paid for the float-generating capabilities of our insurance operations. The cost of the goodwill, however, has no bearing on its true value. For example, if an insurance company sustains large and prolonged underwriting losses, any goodwill asset carried on the books should be deemed valueless, whatever its original cost. Fortunately, that does not describe Berkshire. Charlie and I believe the true economic value of our insurance goodwill – what we would happily pay for float of similar quality were we to purchase an insurance operation possessing it – to be far in excess of its historic carrying value. Indeed, almost the entire $15.5 billion we carry for goodwill in our insurance business was already on our books in 2000. Yet we subsequently tripled our float. Its value today is one reason – a huge reason – why we believe Berkshire’s intrinsic business value substantially exceeds its book value. ************ Berkshire’s attractive insurance economics exist only because we have some terrific managers running disciplined operations that possess hard-to-replicate business models. Let me tell you about the major units. First by float size is the Berkshire Hathaway Reinsurance Group, managed by Ajit Jain. Ajit insures risks that no one else has the desire or the capital to take on. His operation combines capacity, speed, decisiveness and, most important, brains in a manner unique in the insurance business. Yet he never exposes Berkshire to risks that are inappropriate in relation to our resources. Indeed, Berkshire is far more conservative in avoiding risk than most large insurers. For example, if the insurance industry should experience a $250 billion loss from some mega-catastrophe – a loss about triple anything it has ever experienced – Berkshire as a whole would likely record a significant profit for the year because of its many streams of earnings. We would also remain awash in cash and be looking for large opportunities to write business in an insurance market that might well be in disarray. Meanwhile, other major insurers and reinsurers would be swimming in red ink, if not facing insolvency. When Ajit entered Berkshire’s office on a Saturday in 1986, he did not have a day’s experience in the insurance business. Nevertheless, Mike Goldberg, then our manager of insurance, handed him the keys to our reinsurance business. With that move, Mike achieved sainthood: Since then, Ajit has created tens of billions of value for Berkshire shareholders. ************ We have another reinsurance powerhouse in General Re, managed by Tad Montross. At bottom, a sound insurance operation needs to adhere to four disciplines. It must (1) understand all exposures that might cause a policy to incur losses; (2) conservatively assess the likelihood of any exposure actually causing a loss and the probable cost if it does; (3) set a premium that, on average, will deliver a profit after both prospective loss costs and operating expenses are covered; and (4) be willing to walk away if the appropriate premium can’t be obtained. 11